In fact, Sherrod planned to leave for the United States in a

couple of days. “I’m getting too old to stay in combat with these kids,” Pyle

told Sherrod, “and I’m going to go home, too, in about a month. I think I’ll

stay back around the airfields with the Seabees and engineers in the meantime

and write some stories about them.” (Pyle had written a U.S. Navy public

relations officer he knew that he had a “spooky feeling that I’ve been spared

once more and that it would be asking for it to tempt Fate again.”)

As he prepared to leave the Panamint, Sherrod could not find the ship’s mess treasurer, to whom

he owed $2.50 for two days’ meals. Pyle agreed to pay the bill for his

colleague, and asked Sherrod to see about forwarding his mail when he made it

to the American base on Guam. From there, Sherrod began his long voyage home,

traveling to Pearl Harbor, San Francisco, and, finally, New York.

The encounter on the Panamint

marked the last time Sherrod saw Pyle alive, as the Time correspondent left Okinawa on April 11. While in Hawaii,

Sherrod heard the news of Pyle’s death from Japanese gunfire on April 18 while on

a mission with the U.S. Army’s Seventy-Seventh Infantry Division. “I never

learned which doughboy of the Seventy-Seventh Division persuaded Ernie to

change his mind and go on the Ie Shima invasion off the west coast of Okinawa,”

said Sherrod. “But Ernie rarely refused a request from a doughboy, or any other

friend.” The death of Pyle, who Sherrod praised as being better than anyone

else at registering the feeling of the average man about the war, made national

and international headlines, but he was just one of many on Okinawa, American

and Japanese, who lost their lives in some of the costliest fighting of the

war.

By the time major combat operations for Operation Iceberg ceased

near the end of June, more than 12,000 Americans had been killed along with approximately

110,000 of the Japanese military and anywhere from 40,000 to 150,000 civilians.

Offshore, the U.S. Navy had thirty-six ships sunk and 368 damaged due to relentless

Japanese kamikaze attacks. The landscape on Okinawa’s southern line resembled

that of a World War I–era battlefield, with more than 300,000 soldiers and

civilians jammed into an area about the distance between Capitol Hill and

Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C., noted William Manchester, who

served as a sergeant with the Marine Corps and fought on the island. “You could

smell the front long before you saw it; it was one vast cesspool,” recalled Manchester.

“The two great armies, squatting opposite one another in mud and smoke, were

locked together in unimaginable agony.” Eugene B. Sledge of Company K, Third

Battalion, Fifth Marine Regiment, remembered that he and his buddies fought in

an “environment so degrading I believed we had been flung into hell’s own

cesspool.” Sherrod could only reflect on what he had heard during a

pre-invasion intelligence briefing, when an officer said U.S. soldiers and marines

should “expect resistance to be most fanatical.” It was.

Sherrod’s coverage of the last battle in the Pacific war began

with a sober final intelligence briefing on the Panamint, after which “nobody could have felt overconfident.” After

hearing from invasion planners that the Okinawa landings were expected to be

“horrendous—worse than Iwo,” according to Sherrod, Pyle said to him, “‘What I

need now is a great big drink.’ We did have a drink. Many of them.” Ulithi’s

jovial commander, Commodore Oliver Owen “Scrappy” Kessing, had arranged a

farewell party at the officers’ club (the Black Widow) on Asor Island for the

correspondents and high-ranking officers from the navy and First and Sixth

Marine Divisions. The party included a band and, “miraculously,” women—about

seventy nurses from the six hospital ships in the anchorage, plus two women

radio operators from a Norwegian ship. “Everybody got drunk . . . as people

always do the last night ashore,” Sherrod recalled.

The next morning, as the approximately forty reporters and

photographers left Asor for their assigned ships, Kessing had an African

American band on the dock playing its own “boogie-woogie” version of sad

farewell music. Also on hand to see them off was a Seabee lieutenant whose

detachment had built most of the base and a special guest, Coast Guard

Commander Jack Dempsey, the former boxing champion. Someone in the crowd on the

dock shouted out a warning to Pyle—famous for his columns focusing on the

average GIs in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, and France—to be sure to keep his

head down on Okinawa. “Listen, you bastards,” Pyle joked to his colleagues,

“I’ll take a drink over every one of your graves.” Then, he turned to Dempsey,

who, Sherrod noted, weighed about twice as much as the rail-thin reporter, put

up his fists in mock belligerence, and asked the former boxer, “Want to fight?”

It all made for a pleasant trip for Sherrod who, along with Jay Eyerman, a

photographer from Life magazine, had

been assigned to the Coast Guard transport USS Cambria, home also to the headquarters of the Sixth Marine Division.

“This is the smoothest working staff I’ve ever seen,” Commodore Herbert Knowles

said of the marines on the Cambria.

“They know what they want; they know how to load a ship. They don’t have to ask

the general every time a decision has to be made.”

The Sixth Marines needed able commanders if they were to

survive what awaited them on Okinawa, an island sixty miles long and three to

ten miles wide and well within range of bases from which Japanese kamikaze planes

could reach the more than 1,300 U.S. ships involved in the invasion. Lieutenant

General Simon Bolivar Buckner, commander of the Tenth Army, devised a plan in

which two marine divisions (the Sixth and First) and two army divisions (the

Seventh and Ninety-Sixth) would land on west-central beaches near the village

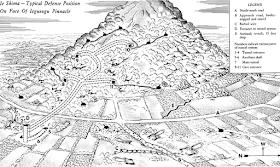

of Hagushi. The island’s topography, especially its mountainous regions on its

southern end near the ancient castle town of Shuri, made it ideal for Japanese

forces of the Thirty-Second Army under the command of Lieutenant General Mitsuru

Ushijima to construct fortifications in caves and bunkers that could rain

destruction upon the advancing enemy.

The Japanese planned on letting the

Americans land unopposed, then isolate them ashore to be annihilated in a

“decisive battle” once the fleet had been destroyed by kamikaze attacks from

both the sea and air. After the fighting ended, U.S. troops discovered that in

just one sector of the enemy’s defenses they had faced sixteen grenade

launchers, eighty-three light machine guns, forty-one heavy machine guns, seven

47-mm antitank guns, six field guns, two mortars, and two 70-mm howitzers. The

Japanese soldiers on Okinawa took as their motto: “One plane for one warship,

one boat for one ship, one man for ten of the enemy or one tank.” Okinawa

itself stood as a formidable obstacle to a successful invasion, noted Sherrod.

“The island abounded in flies, mosquitoes, mites, rats, and poisonous snakes,”

he said.

While awaiting the invasion on his transport, Sherrod spent

several hours listening to propaganda broadcasts from Radio Tokyo, a station he

had first come across while at sea with the U.S. Third Fleet before the

invasion of Iwo Jima. Radio Tokyo’s broadcasts were made in English every hour

on the hour, usually in the afternoon, and featured commentaries on Japanese

achievements in science and newscasts slanted toward home consumption, as well

as providing “aging popular music” and messages from American and British

prisoners of war made under pressure. “Anyone listening exclusively to

Radiotokyo could only conclude that Japan is winning the war,” said Sherrod.

“Radiotoyko permits no admissions of death or of retreat such as even [Nazi

propaganda minister Joseph] Goebbels must sometimes make.”

Even before the U.S.

fleet reached Okinawa, Radio Tokyo claimed that its forces had sunk an American

battleship, six cruisers, seven destroyers, and a minesweeper. The broadcasters

for the “Zero Hour” program Sherrod listened to on the Cambria interspersed their wild reports of success with banter and

music. Before playing a song titled “Going Home,” one of the broadcasters

introduced the tune as a “little juke-box music for the boys and make it hot,

because the boys are going to catch hell soon, and they might as well get used

to the heat.” The Japanese broadcasters failed in their attempt to strike fear

into the hearts of their audience. Sherod noted that the few sailors who sat

around the communication room on the transport listening to Radio Tokyo “acted

as bored as men who had seen a Grade B movie three times.”

Sherrod could never have anticipated what awaited the marines

and soldiers when they landed on Okinawa on April 1, Easter Sunday and April

Fool’s Day. It proved to be quite an April Fool’s prank by the Japanese. Early

on, it looked like the reception on the beaches would be hot, as kamikazes were

active seven hours before the start of the invasion. “Many times before

daylight the sky around us was pierced by anti-aircraft tracer bullets, but no

enemy planes got within shooting distance of the Cambria,” said Sherrod. The suicide planes did cause some damage to

the transport USS Hinsdale and two

Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs) carrying troops of the Second Marine Division making

a diversionary demonstration south of Okinawa. The U.S. troops who landed ashore

on L-Day (Love-Day in the voice signal alphabet), however, “stepped ashore with

slightly more opposition than they would have had in maneuvers off the coast of

California. To say merely that they were bewildered is to gild the lily of

understatement,” Sherrod observed.

Missing from the landing beaches on the west coast from

north of Kadena southward halfway to Naha was the usual deadly rain of

withering machine-gun fire, nine-inch rockets, and 320-mm mortars. Within three

hours, the First Marine Division had taken Yontan Airfield against only a few

shots from isolated snipers at a cost of two killed and nine wounded. At 10:00

a.m. Sherrod wrote in his notebook: “This is hard to believe.” The news was the

same for the soldiers, with the Seventh Division stepping from their amtracs

onto a seawall “as easily as if they had been on a pleasant fishing trip,”

noted the correspondent. The soldiers moved on to capture Katena Airfield after

disposing of a solitary machine-gun position.

On Okinawa, Sherrod discovered

half-heartedly constructed pillboxes, most of which seemed to have been

abandoned long ago. “Only a few [mortar] bursts were fired at the landing

amtracs, and none of them caused any casualties,” he said. A relieved Vice

Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner radioed a message to Admiral Chester Nimitz in

Hawaii that read: “I may be crazy but it looks like the Japanese have quit the

war, at least in this sector.” The more realistic Nimitz responded: “Delete all

after ‘crazy.”

Sherrod, too, expected stiffer opposition to come, realizing

that the Japanese had “given up their beaches above Naha and moved farther

south.” What nobody could foresee on the invasion’s first day, or in the two

weeks that followed, was that the enemy “would have the strength to fight as

fiercely as they finally did—else why had they let us ashore so easily?” he

asked. A marine officer proved to be prophetic when he said to Sherrod: “This

is the finest Easter present we could have received. But we’ll get a bellyful

of fighting before this thing is over.”

No comments:

Post a Comment