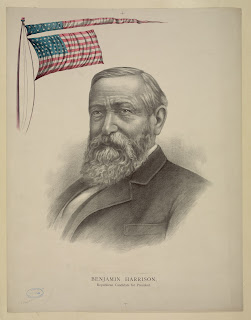

The crowds that flocked to

Indianapolis in 1888 came to visit a man who, from an early age, seemed destined

for political greatness. Benjamin Harrison was the son of John Scott Harrison, a two-term congressman from Ohio;

grandson of William Henry Harrison, the first governor of the Indiana Territory

and ninth president of the United States; and the great-grandson of Benjamin

Harrison V, governor of Virginia and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Benjamin Harrison captured the presidency that year, defeating incumbent Grover

Cleveland.

The future twenty-third

president was born on his grandfather’s farm at North Bend, Ohio, on August 20,

1833. After receiving his early education at Farmers’ College in Cincinnati,

Harrison graduated from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, in 1852. After

graduation, the young man studied law for two years with a Cincinnati firm and

married Caroline Lavinia Scott , an

Oxford Female Institute graduate and an accomplished artist and musician. In

1854 the twenty-one-year-old Harrison and his wife moved to the growing city of

Indianapolis, and Harrison established his own law practice.

Given Hoosiers’ love of

politics, and the famous Harrison name, the young lawyer became drawn—somewhat

reluctantly—into the political scene. In 1856 while busy working at his law

office, Harrison was interrupted by some Republican friends who dragged him

from his office to speak before a political gathering. Introduced to the crowd

as the grandson of “Old Tippecanoe,” Harrison firmly replied: “I want it

understood that I am the grandson of nobody. I believe that every man should stand

on his own merits.”

The Harrison family’s strong

political background, however, did aid young Harrison as he undertook a

political career, becoming Indianapolis city attorney in 1857 and being elected

to the post of Indiana Supreme Court reporter three years later. The Civil War

halted Harrison’s political career. Asked by Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton

to recruit men for the Seventieth Indiana Volunteer Infantry, Harrison served

as a colonel with that outfit and offered sterling service to the Union cause

in the battles of Peach Tree Creek and Resaca, Georgia. During the war Harrison

received the nickname “Little Ben” from his troops (he stood five feet, six

inches tall).

In a one-month period during

the Union’s fight to take Atlanta, Harrison, now in charge of a brigade of

regiments that included the Seventieth, had participated in more battles than

his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, had fought during his lifetime. At New

Hope Church, Georgia, Harrison had his troops fix bayonets to attack the enemy

position “Men, the enemy’s works are just ahead of us, but we will go right

over them. Forward! Double-quick! March!” he ordered.

In a one-month period during

the Union’s fight to take Atlanta, Harrison, now in charge of a brigade of

regiments that included the Seventieth, had participated in more battles than

his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, had fought during his lifetime. At New

Hope Church, Georgia, Harrison had his troops fix bayonets to attack the enemy

position “Men, the enemy’s works are just ahead of us, but we will go right

over them. Forward! Double-quick! March!” he ordered.

After a bloody action at

Golgotha Church near Kennesaw Mountain on June 15—fighting where two or three

of his men had their heads torn off down to their shoulders—Harrison pitched in

to help with the wounded, as the brigade’s surgeons had scattered in the

fighting. “Poor fellows!” Harrison said of the casualties who had taken shelter

in a frame house. “I was but an awkward surgeon of course, but I hope I gave

them some relief,” he wrote Caroline. The colonel treated some “ghastly wounds,”

including pulling from a soldier’s arm a “splinter five or six inches long and

as thick as my three fingers.” He also ordered tents to be torn up so the

strips of cloth could be used to bandage the wounded.

Mustered out of the Grand

Army of the Republic with a brevet brigadier general’s commission, Harrison

returned to Indianapolis to fill out his term as Indiana Supreme Court reporter

before returning to his private law practice. Paradoxically for Harrison, his

biographer Harry J. Sievers noted, the financial panic that gripped the country

in the early 1870s aided his firm as “defaults, mortgage foreclosures, and

bankruptcy cases flooded the office.”

Financially secure, Harrison

turned his attention to building a new home for his family, which included at

that time two teenage children, Russell and Mary. In 1867 Harrison had

purchased at auction a double lot on North Delaware Street, and it was here

that the family’s new red brick home was built during the fall and winter of

1874 and 1875 at a cost of approximately $20,000. Along with a library for

Harrison’s substantial book collection, the home possessed a ballroom and

became a popular location for society events, including Thursday afternoon teas

hosted by Caroline Scott Harrison,

first president-general of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

In 1876 Harrison returned to

the political arena, running as the GOP candidate for Indiana governor. He lost

to Democrat James “Blue Jeans” Williams; his electoral failure, however, did

not hurt his strong standing with Hoosier Republicans. In 1881 the Indiana

legislature, controlled by the GOP, elected Harrison to serve a six-year term

in the U.S. Senate. Harrison arrived on the national scene at an

opportune time where Indiana played a prominent role on the national political

scene following the Civil War. To attract Hoosier voters, political parties

often selected “favorite sons” from Indiana to bolster the parties’ chances in

November.

In 1888 the Republican Party

nominated Harrison as its presidential candidate. Like most presidential

contenders of that time, Harrison refused to barnstorm around the country for

votes, preferring instead to remain at home. “I have a great risk of meeting a

fool at home,” he told journalist Whitelaw Reid, “but the candidate who travels

cannot escape him.”

While

Cleveland remained in the White House, content with his duties as president and

believing in the dictum “the office sought the man,” Harrison embarked on a

busy speaking schedule that saw him give more than eighty extemporaneous talks

to more than 300,000 visitors to Indianapolis from July 7 to October 25.

Usually, there were anywhere from one to three delegations per day, but at one

point Harrison met seven on one day. To meet the demand posed by those who

clamored to see the candidate at his Indianapolis home, a “committee of

arrangements” was formed to manage the deluge of letters sent to Harrison and

to schedule and control visitors.

The

crowds soon overwhelmed the space at the Delaware Street house, and instead

were moved about a mile away to University Park, the former drilling ground for

Union soldiers. Marching bands were on hand at Union Station to welcome

delegations as they arrived and accompanied them as they walked to the park.

All the remarks made by outside groups were closely scrutinized to ensure that

no controversial statements were uttered, and Harrison listened to them and

often adjusted his speech to reflect what had been covered. Delegations included

such groups as commercial travelers, Union war veterans, railroad workers,

African American supporters, young girls who had formed a Harrison Club, and

old followers of William Henry Harrison’s 1840 presidential campaign.

Although

at the beginning of the campaign Harrison had called for the two parties to

“encamp upon the high plains of principle and not in the low swamps of personal

defamation or detraction,” his hopes were dashed by the 1888 election’s two

great controversies—one that damaged Cleveland’s chances, and one that hurt

Harrison.

The first broadside came in October with what became known as the MurchisonLetter. A California Republican had sent a letter, signed as Charles F. Murchison,

to Sir Lionel Sackville-West, the British minister (ambassador) to the United

States, asking his advice on how to vote. Not suspecting a trap, Sackville-West

answered the letter with friendly words and support for the Cleveland

administration as the best choice for British interests despite recent tensions

over a dispute regarding fishing rights in Canada. Republican officials

released Sackville-West’s letter to the press. The seemingly friendly relations

between the hated British and the Cleveland administration infuriated

Irish-American voters in New York, and Cleveland had to call for Sackville-West

to be dismissed.

Shortly

after the Murchison Letter had caused such a furor, the Democrats struck

political gold with another letter, this one involving William W. Dudley, the

Republican National Committee treasurer, and featured the class of voter known

as a “floater,” a person with no fixed party allegiance who sold his ballot to

the highest bidder, be it Republican or Democrat. Party workers could buy these

votes for as little as two dollars or as high as twenty dollars in close

elections, and since political parties, not the state, printed and furnished

ballots to voters, could ensure that once a “floater” was bought, he stayed

bought. “This infamous practice,” complained the Shelbyville Republican, “kept up year after year by both parties,

has brought about a state of affairs that cannot be contemplated without a shudder.”

The newspaper went on to lament that a third of the state’s voting population

“can be directly influenced by the use of money on the day of election.”

In a letter sent to an Indiana Republican

county chairman, Dudley warned that “only boodle and fraudulent votes and false

counting of returns can beat us in the State [Indiana].” To counter this

threat, he advised Republican workers to find out what Democrats at the polls

were responsible for bribing voters and steer committed Democratic supporters

to them, thereby exhausting the opposition’s cash stockpile. The most damaging

part of the letter, however, appeared in a sentence where Dudley advised:

“Divide the voters into blocks of five, and put a trusted man, with necessary

funds, in charge of these five, and make them responsible that none get away.”

The

political dynamite in Dudley’s letter found its way to the opposition thanks to

a Democratic mail clerk on the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad who was suspicious

about the large amount of mail being passed from Republican headquarters to

Indiana Republicans. He opened one of the letters, recognized its value to his

party, and passed the damaging contents to the Indiana Democratic State Central

Committee. The Sentinel printed the

letter on October 31, 1888, under a banner headline reading: “The Plot to Buy

Indiana.”

Although an indignant Dudley and other top Republican officials declared

that the letter was a forgery, and denounced the person responsible for

interfering with the mail, its contents received nationwide attention, with

newspapers supporting the Democratic cause, including the Sentinel, happy to lambast Harrison for his ties to such chicanery,

while Republican papers defended their candidate’s character. A political

veteran such as Michener said that the instructions Dudley outlined were

standard practice by both parties in Indiana, and found nothing in the letter

“unusual, illegal or immoral.”

What effect both scandals had on the

campaign’s outcome is still debated by historians, with Charles Calhoun, in his

book on the 1888 election, arguing that underhanded practices by both parties

in New York and Indiana “may well have canceled each other out," while racist voting restrictions in the South blocked most African Americans from casting ballots for Republican candidates.

Whatever the

impact nationally, in Indiana the Dudley letter had failed to dampen the enthusiasm

of Hoosier Republicans for their favorite son. The day before the election,

Harrison, on his way to his downtown law office, was greeted with applause and

cheering. On Election Day, Tuesday, November 6, Harrison walked from his home,

accompanied by his son, Russell, to Coburn’s Livery Stable at Seventh Street

between Delaware and Alabama Streets, the polling place for the third precinct

of the second war. To a cry from a supporter of “There comes the next

President,” Harrison cast the ballot he had carried with him from his home.

After

voting, Harrison returned home to learn his fate as a candidate, with regular

reports coming to him in his library through a special telegraph wire

connecting him with Republican headquarters in New York. After the polls

closed, downtown streets in Indianapolis were clogged with people eager to hear

the results, with many gathering near newspaper offices to receive reports. “As

the morning drew nearer,” noted an article in the Indianapolis Journal, “the wild crowd, growing hilarious with

excitement, would receive a return with cheers, and the next moment follow it

up with a refrain of ‘Bye, Grover, bye; O, good-bye, old Grover, good-bye.’

Another return, and ‘What’s the matter with Harrison? He’s all right.”

Several

people gathered around a large, oval writing table in Harrison’s library to read

over the returns. When vote totals arrived over the wire from New York, they

were read aloud, sometimes by Harrison and sometimes by his law partners, while

Russell sorted bulletins by state. The Journal

described the scene as “a quiet gathering of a few neighbors,” adding that

Harrison seemed “cool and self-possessed,” sometimes retreating to the parlor

to talk with his wife, Caroline, and her guests. According to one account, when

returns from the state of New York seemed discouraging, Harrison took the news

well, telling his friends to cheer up. “This is no life and death affair. I am

very happy here in Indianapolis and will continue to be if I’m not elected.

Home is a pretty good place.”

Harrison

seemed much more concerned about whether he won Indiana, closely perusing

returns from each of the state’s ninety-two counties. When his son-in-law, at

about 11:00 p.m., announced that it looked as if Indiana had been won, Harrison

responded: “That’s enough for me tonight then. My own State is for me. I’m going

to bed.”

At the White House, Cleveland also monitored the election results. At

midnight in Washington, D.C., Secretary of the Navy William Collins Whitney,

walked out of the telegraph room and down a corridor to announce: “Well, it’s

all up.” Asked the next morning how he could go to sleep still not knowing

whether he had won the presidency, Harrison noted that his staying up would not

have changed the results if he had lost, and if he won he knew he “had a hard

day ahead of me. So I thought a night’s rest was best in any event.”

The

Hoosier candidate won the presidency, securing the Electoral College with 233

votes to 168 for Cleveland. Harrison had been able to grab the crucial states

of New York and Indiana, winning both by the barest of margins (by 2,376 votes

in the Hoosier State and 14,373 votes in New York; in both states turnout

exceeded 90 percent); both of these were states that Cleveland had captured in

the 1884 election. In the popular vote, Cleveland bested Harrison, with

5,534,488 votes to 5,443,892 for his opponent, becoming the third of five

presidential candidates to win the popular vote but lose in the Electoral

College (the other losing candidates were Andrew Jackson in 1824, Samuel Tilden

in 1876, Al Gore in 2000, and Hillary Clinton in 2016).