On the eve of Election Day in November 1974, Kathy Altman,

volunteer

White County

coordinator for Democratic candidate

Floyd Fithian’s successful run to

represent the Second Congressional District against incumbent Republican congressman

Earl Landgrebe, was driving back with her husband, Jerry, to their house in

Monticello,

Indiana.

The couple had just finished a long day’s work setting up a get-out-to-vote

effort on Fithian’s behalf. Suddenly, the car’s headlights flashed into the rainy

darkness and lit upon a lonely figure trudging down the road—Jim Jontz, a young,

first-time candidate for the Indiana House of Representatives.

Jontz had been staying at the Altman’s home while engaging in

a dogged door-to-door campaign in the four counties of the Twentieth District.

Altman and her husband asked him if he needed any help. “No, it’s late,” Altman

remembered Jontz responding, “but there’s a laundromat up there that’s still

open I think I’ll go hit before I quit for the night.”

The next day Jontz, a twenty-two-year-old Indiana University

graduate with an unpaid job as a caretaker for a local nature preserve,

defeated his heavily favored Republican opponent, John M. “Jack” Guy, Indiana

House majority leader. “I must have knocked on half the doors in the district,”

Jontz said of what he called a “shoe-leather” campaign. “And I found that

people like to have someone come to their door and talk to them, even if it is

a young kid. I told them that I wasn’t a lawyer or politician, but that I was

interested in people, in dealing with them personally. And that was about it.” Jontz

had entered the race in the majority Republican district in large part to

oppose a multi-million-dollar U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dam project on Big

Pine Creek near Williamsport, Indiana. He had gone to bed on election night

believing he had lost after hearing a report from the final precinct in Warren

County indicating that he had been defeated by a scant two votes. The next

morning he awoke to learn that there had been an error and he had won by the

same slim margin. “One more vote than I needed to win!” he later exclaimed. The

unexpected result stunned election officials, with one deputy clerk in Warren County

marveling, “I never before realized just how important that one vote can be.”

Jontz’s initial run for office, which saw him survive two

recounts to secure his legislative seat, set the standard for his subsequent longshot

political career. As a liberal Democrat (he preferred the term progressive)

usually running in conservative districts, Jontz had political pundits predicting

his defeat in every election only to see him celebrating another victory with

his happy supporters, always clad in a scruffy plaid jacket with a hood from

high school that he wore for good luck. “I always hope for the best and fight

for the worst,” said Jontz. He won five terms as state representative for the

Twentieth District (Benton, Newton,

Warren, and White counties), served two years in

the Indiana Senate, and captured three terms in the U.S. Congress representing

the sprawling Fifth Congressional District in northwestern Indiana

that stretched from Lake County in the north to Grant County

in the south. Jontz told a reporter that his political career had always “been

based on my willingness and role as a spokesman for the average citizen.”

Jontz managed to win re-election in the Republican district thanks

to a combination of tireless campaigning; a relentless focus on serving his

constituents through such activities as town hall meetings, a toll-free number

for those wishing to question their congressman, and face-to-face encounters at

neighborhood coffee shops at all hours of the day; and a willingness to listen

to dissenting opinions. “You have to disagree sometimes,” he noted. “But you

have to disagree agreeably.” Tom Sugar, a longtime Jontz aide, called the

congressman “very, very politically savvy, not in a sense that he manipulated

voters, I don’t mean that. What I mean is, he knew the people he cared about

and learned their issues very deeply. And he sincerely fought for their

interests. And he fought for the interests of his district.” Tom Buis, an

agricultural policy expert on the congressman’s staff, remembered returning

late at night to the

Longworth House Office Building in Washington, D.C., only

to find Jontz still at his desk reading every letter that went into and out of

his office. “If his constituents were paying him by the hour, he was working

for less than minimum wage,” said Buis, “because he worked around the clock.

They got their money’s worth.”

Each election season voters in Jontz’s congressional district

could count on hearing a knock on their front door and seeing the rumpled, tousle-haired

Democrat ready to promote his candidacy and talk about whatever issue that

might concern them that year. “Jim believed in knocking on every door that was

knockable,” said Sugar, who went on to serve as chief of staff for U.S. Senator

Evan Bayh. Whenever a community in his district hosted a parade, Jontz could be

found riding the route on his sister’s rusty, old blue Schwinn bicycle with

mismatched tires, waving to the crowd lining the streets, his tie flapping in

the breeze—an effort that won him the title of “best congressman on two wheels”

from one Indiana reporter. (Jontz’s record was riding his bicycle in seven

Fourth of July parades in one day.) The national media also paid attention,

finding Jontz to be a good story, noted Scott Campbell, who served as the

congressman’s press secretary. “There were other liberal Democrats in the U.S.

Congress, there were other conservative districts in the U.S. Congress, but the

number of solidly Republican districts represented by liberal Democrats was a

number you could count on your hand,” said

Campbell.

Christopher Klose, who managed Jontz’s first run for

Congress and served as his chief of staff in Washington, D.C.,

called his former boss “a true populist,” noting he could be just as

distrustful of mindless government as he could of reckless corporate behavior.

He remembered Jontz saying that issues needed to be examined from “top to

bottom, not left to right.” One of Klose’s favorite memories of Jontz is one

culled from the campaign trail. After another long day and night seeking votes,

the candidate, after packing up his car for the next day’s schedule of events,

uttered what came to be known to his staff as the Jim Jontz prayer. “Jim would

just shake his head and look up and say, ‘Lord, help me win this one, and I

promise next time we’ll do it right,’” Klose said.

This single-minded devotion to serving the voters—he kept a

homemade sign given to him by a supporter in his Washington, D.C., office that

read “This office belongs to the people of Indiana’s 5th District”—came with a

price in his private life, as Jontz endured two divorces. “He always had a

goal,” said his first wife, Elaine Caldwell Emmi, who today lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

“He knew exactly what he wanted to do.” She recalled one conversation with her

husband as their marriage was falling apart in which she told him that every

morning she awoke questioning if this is what she wanted to be doing and how

should she lead her life. “He looked at me and said, ‘I never ask that

question. I know exactly what I should be doing,’” Emmi said. “I think he

really liked being a public official, a servant of the people—that was really

his goal.” Being a congressman, noted one of Jontz’s aides, became his

“all-consuming passion.”

From an early age Jontz, the eldest of two children born to

Leland, an Indianapolis businessman, and Pauline (Polly) Jontz, displayed a

penchant for organization and a dedication to nature while growing up in the

1960s in the Northern Hills subdivision on the city’s north side—a “semirural

setting” that enabled him to develop his interest in the outdoors. “Mom

encouraged me to chase butterflies, and we bought all the Golden [Nature]

guidebooks,” Jontz said. Polly, who worked at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis

and for many years as president of the Conner Prairie Pioneer Settlement,

remembered her son as “a very intense child, very curious, very serious, [and] very

focused.” Jontz’s kindergarten teacher told his mother that he had been the

only student she had taught “who had the dignity to be president of the United States.”

He also displayed the leadership qualities that served him well during his

political career, organizing the neighborhood children for impromptu football

games and bicycle races. “He was a fun young man to know because he was

interested in everything,” said Polly.

On family trips during the summer to historic sites and

national parks, Jontz made sure to add to his growing rock collection by

stopping at every rock store on the route and hunting for geodes along the

roadside with his pickaxe, noted his sister, Mary Lee Turk. His other hobbies

included music (Jontz played the piano, trombone, and French horn) and a

devotion to the ideals of the Boy Scouts of America as a member of Troop Number

117, earning the rank of Eagle Scout while in the seventh grade. “My main aims

now are to receive a good education, to become an asset to my community and a

good citizen, and to live up to the Scout oath and law,” Jontz wrote in his

application for Eagle Scout. When he was older, Jontz continued to support the organization,

working summers at Camp Belzer, a Boy Scout reservation near Lawrence, Indiana.

He also maintained his interest in the outdoors by leading nature hikes through

Indianapolis

parks for the Children’s Museum and serving as a naturalist for the Indiana

State Parks system.

Jontz’s interest in nature meant that there were often wild

animals roaming the family’s home at 1141 East Eightieth Street. Camp Belzer

had a small zoo with rescued wild animals. At the end of one summer, Jontz

brought home with him a de-scented skunk he named Jerome. Although his father

built a cage for the skunk, it sometimes escaped. During one try for freedom

the skunk hid under a bed and bit Leland on the finger when he attempted to

retrieve it and return it to its enclosure. Other members of Jontz’s wildlife

menagerie included a hawk that Jontz fed raw meat and a squirming mass of baby

rattlesnakes. “You never knew what would be in our house,” noted Turk.

From his parents Jontz learned the lesson of always

following his convictions but expressing disagreement within established

structures. Both Polly and Leland Jontz were staunch Republicans, and were

surprised to hear their son note, after saying something to him about your

party, meaning the GOP, “Mom, I’m a Democrat.” Despite their political

differences, his parents supported Jontz’s quest to find a suitable vocation

for his devotion to hard work and wide knowledge. After graduating from North

Central High School, Jontz entered Williams College, a small liberal-arts institution

in Massachusetts, but spent only one semester there, calling it “too academic”

for his tastes. “I read 12 hours a day there,” Jontz recalled of his time at

Williams. “I had had enough of that, so when I came to I.U. [Indiana University]

I had some spare time.”

In January 1971 Jontz enrolled at IU in Bloomington, where he majored in geology and lived

in Wright Quad with a freshman named Bob Rodenkirk. A native of Chicago, Illinois,

Rodenkirk originally had been roommates with a relative of Philippine dictator

Ferdinand Marcos, who very quickly flunked out of the university after spending

more time enjoying himself than studying. Jontz proved to be quite different,

with Rodenkirk describing him as a serious and driven student, especially when

it came to environmental issues. “I can’t remember a time when he didn’t have a

to-do list a half a mile long,” said Rodenkirk. As more and more Americans became

concerned with conserving the country’s natural resources, Jontz responded by

spending a large amount of his time with the Biology Crisis Center, a student

group working on conservation and environmental affairs in the Bloomington area.

With the center he worked on such issues as the belching black smoke from the

university’s coal-fired power plant, a sinkhole that had emerged in front of

Wright Quad, how IU disposed of plastic foodware, the ecology of the Jordan

River, and opposing a dam that threatened the Lost

River in Orange County.

Tracking down Jontz during his days at IU could be

problematic, as he spent little time in his dormitory room, getting by on just

four to five hours of sleep per night—a schedule he kept in later years (one of

his favorite quotes was “early to bed, early to rise, work like hell and

organize”). Through his work on environmental issues, Jontz became very

involved in state politics, helping to write the conservation and recreation

platform for the Indiana Democratic Party and serving on an environmental

education task force created by State Superintendent of Public Instruction John

J. Laughlin. Even when he was in his dormitory room, Jontz received little

rest, fielding questions from such noted Hoosier political figures as

Governor Otis Bowen and

U.S.

Senators

Birch Bayh and

Vance Hartke. “The phone calls I would take from Jim

were amazing,” remembered Rodenkirk. What scared Rodenkirk was Jontz’s habit of

reading a textbook lying open on his lap while driving back and forth from

Bloomington to

Indianapolis

to lobby on behalf of the environment at the Indiana Statehouse. Jontz always

made it back safely, and Rodenkirk was “amazed at how much information he could

process. He was a born leader.”

Jontz’s work on environmental matters at the university

brought him into contact with another student activist, Emmi, the daughter of

Lynton K. Caldwell, a nationally known professor of political science at IU

famous for being one of the principal architects behind securing environmental

impact statements for federal projects. Although Emmi had observed Jontz in

geology and folklore classes they shared, the two did not become close until she

helped arrange a trip with other IU students to Washington, D.C.,

to lobby on wilderness issues before a U.S. Senate subcommittee for an environmental

law class she was taking. Through her father she was able to find

accommodations for the group in the basement of a church on Capitol Hill for

just seventy-five cents a night. “He really wanted to make a difference,” Emmi

said of Jontz, whom she married in June 1973.

Although she hated public speaking, Jontz relished such

events. “And he got better at it every day,” she said. “He remembered

everyone’s name and took delight in walking into a room full of people as no

one was a stranger—there just were people he hadn’t yet befriended.” Although

it might sound too grandiose to say that Jontz wanted to save the planet, Emmi

noted “that was his ultimate goal, to be a spokesman for those that couldn’t

speak—the trees, the animals, the air, the water.”

Graduating from IU in 1973 with Phi Beta Kappa honors, Jontz

worked for a few months in Chicago as program director for the Lake Michigan

Federation before returning to his home state as conservation director for the

Indiana Conservation Council, where he also edited the organization’s monthly

newsletter. A potential ecological threat in Warren

County, however, soon drew Jontz and

his wife to northwestern Indiana.

As far back as the 1930s, there had been proposals to build a dam and reservoir

on Big Pine Creek, which flowed from southwestern White

County south through Benton and Warren

counties before entering the Wabash River near Attica,

Indiana. Along its route the

creek flowed along scenic sandstone cliffs and Fall Creek Gorge, noteworthy for

the large potholes carved into the floor of the steep-sided canyon. In October

1965 Congress, in its Flood Control Act, authorized the Army Corps of Engineers

to build an earth and rockfill dam on Big Pine Creek at an estimated cost of

$28 million. The resulting reservoir would cover more than a thousand acres northeast

of Williamsport, Indiana.

The project, which received support from Republican

congressman John T. Myers representing the Seventh Congressional District, drew

protests from state environmental groups and several citizens in Warren County

(a mail poll taken by a local newspaper has residents against the dam by a

ten-to-one margin). Local groups opposing the project, including the Committee

on Big Pine Creek and the Friends of the Big Pine Creek, charged that the dam

and its reservoir would engulf sixty homes, ten commercial properties, 2,347

acres of cropland, 2,200 acres of pastureland, and 1,995 acres of woodlands.

Hoping to protect a portion of the area from destruction, the Nature

Conservancy, with the help of a $20,000 loan from a Purdue

University janitor, bought a forty-three-acre

site in Warren County, property that included Fall

Creek Gorge. The conservancy hired Jontz to serve as caretaker and program

director for the property. He lived in a handmade house near the preserve with Emmi,

two dogs (Brother and Sister), and two cats (Vance and Birch, named for Indiana’s two U.S. senators at that time).

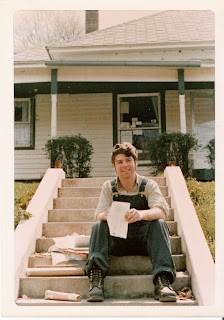

Often dressed in his trademark blue-jean overalls, Jontz

quickly became one of the leaders in the fight against the Big Pine Creek dam, dominating

a Corps of Engineers hearing on the project and appearing in the forefront of a

protest held during a fund-raising golf event for Congressman Myers that saw

dam opponents cruise around the country club in a mile-long caravan of cars,

pickup trucks, motorcycles, and farm implements. Protestors confronted Myers

with signs reading “Only You Can Prevent Forest Floods” and “Dam the Corps.” Bill

Parmenter, who served as president of the Committee on Big Pine Creek, remembered

Jontz as outgoing, friendly, and possessed with real leadership qualities. “He

could make people do things—more than they thought they would be able to do,”

said Parmenter, who lived to see the federal government finally abandon the dam

project for good in the early 1990s.

To help give voice to those opposing the dam, Jontz

attempted to find someone to run for the state legislature against incumbent

Guy, a Monticello attorney, in the rural district. Unable to secure a candidate

for the Democratic nomination, he approached party leaders in the area and told

them he wanted to run. “They were tickled to death that someone wanted to do

it,” Jontz said. With help from his wife and a few friends, Jontz began a shoe

leather, door-to-door campaign, visiting every house in such small communities

in the district as Boswell, Brook, Brookston, Chalmers, Fowler, Goodland, Kentland,

Monon, Morocco,

Otterbein, Oxford, Otterbein, Reynolds, West Lebanon, Wolcott, and many others. He also attended

every fish fry he could find and three straight weeks of county fairs, shaking

hands with countless potential voters. “I campaigned on the personal attention

idea,” Jontz said. “Issues are important to people, but more important to them

is feeling that government is responsive.”

After his razor-thin win over Guy in the general election,

Jontz worked as hard during his days as a legislator as he had during the

campaign. When the legislature was not in session, he could be found back in

the district, attending meetings of service clubs and any other local event he

could find. Jontz often talked with voters and turned their concerns about

issues into legislation. After speaking with a grade school teacher in Wolcott,

Jontz introduced a bill requiring reading and writing tests for high school

graduates, an idea that became law. He and his wife also scoured every

newspaper in the four-country district, clipping out articles about people in

the news, pasting them onto official stationery, and having Jontz write a

personal note congratulating them on whatever honor they had achieved. “Sometimes

we would be up very late at night and get really silly,” Emmi said, “concocting

imaginary headlines—‘County Commissioner Arrested for Stealing Hubcaps’ or

‘Honor Student Arrested for Prostitution Ring.’ You can imagine the gales of

laughter that resulted.”

As a full-time legislator serving in a state where most

members of the general assembly have other jobs, Jontz worked long hours when

the legislature was in session. Many of his fellow Democrats sought his

expertise on such issues as the environment and health care. Stan Jones, who,

like Jontz, won his first Indiana House race in 1974 while in his twenties,

noted at first the two of them were sometimes mistaken for young pages by the

older lawmakers. He called Jontz a “very responsible legislator. He didn’t miss

votes, he came to every committee meeting, read bills—not every legislator read

bills.” Frequently, at the start of a day’s work in the House, Jones said that

Jontz would walk in with eight to ten amendments for legislation he would then parcel

out to other representatives to introduce. During one session in the 1980s, Jontz convinced another Democratic legislator to introduce an amendment

forbidding utility companies from charging their ratepayers for unfinished

power plants—a feature that became law.

Other issues Jontz found success with included nursing home

reform; child, spouse, and elder abuse laws; preventive health screening; solar

energy tax credits; a state cancer registry; residential programs for the

chronically mentally ill; and the state’s unified tax credit for the elderly.

“I think people [legislators] were pretty frustrated with him, but he was very

effective,” Jones said of his fellow Democrat. “He was just determined to get

things accomplished and it really didn’t matter to him that they might be upset

by that.”

In 1986 GOP congressman Elwood “Bud” Hillis, who had

represented the Fifth Congressional District since 1971, announced he would not

seek re-election. Jontz captured the Democratic nomination for the position and

faced fellow state senator James Butcher of Kokomo. Sugar, a Howard County

native whose parents supported Butcher and even held a fund-raiser for him in

their home, recalled receiving a call from Alan Maxwell, his political science

professor at IU Kokomo, saying there was a candidate running for Congress who

needed his help in organizing the county. His first meeting with Jontz occurred

at the Howard County 4-H Fairgrounds. “I’d seen a

photo of Jim in the paper before and, bless his heart, he wasn’t the most

telegenic guy in the world,” said Sugar, who had never participated in a

political campaign. Impressed by the candidate’s passion for issues, he agreed

to help with his door-to-door efforts in the county, assisted by local members

of the United Auto Workers and environmentalists from Indianapolis.

On a typical day, Jontz started knocking on doors on one

side of the street beginning at three in the afternoon, with Sugar or another

campaign aide taking the other side. The usual spiel included introducing

themselves, telling a homeowner that Jontz was campaigning in the area, and

giving them material on his candidacy. If someone did not answer, Jontz would

leave behind his literature with a note signed, “Sorry I missed you, Jim.”

Sugar said that the rule of thumb was that the campaign did not “stop knocking

on doors until people started showing up [dressed] in robes.” After completing

their first canvas of the county, every house that could be visited, Sugar

quoted Jontz as indicating, “‘OK, let’s do it again.’ So we did it again.” Two

days before the election, the second canvas had been completed, but Jontz

decided to do it again. “He believed in working until the last dog died,” said

Sugar.

Just hours after the polls closed on November 4, 1986, with

Jontz defeating Butcher 80,722 (51.4 percent) to 75,507 (48.1 percent), the new

congressman found Sugar as the celebration at campaign headquarters in

Monticello was winding down and told him he wanted to visit a Chrysler plant in

Kokomo the next day to thank the workers for their support. Bright and early

the next morning, after only a few hours of sleep, Jontz stood at the plant’s

gate to greet the groggy automotive workers as they started their early shift,

jolting them awake with his words: “Hey, thanks a lot guys, I won’t let you

down. I really appreciate your support yesterday, I will not forget.” Most of

the workers acted as if this was the first time a candidate had ever thanked

them personally for their vote just hours after winning an election. “It was an

example of everything our campaign stood for,” said Sugar. “We meant it. We’re

really going to fight for working folks.”

Jontz ran his four-room congressional office to emphasize

constituent service, placing more staff members in the district back in Indiana

than in Washington, D.C., helping veterans, Social Security recipients, and

farmers. In comparing notes with other chiefs of staff, Klose found that his

office had a far greater constituent caseload than any other delegation, with

the closest office handling only a third of the casework Jontz’s office did.

“Every time he [Jontz] would go out and say, ‘Tell me your problems,’ there

were plenty of problems people wanted to tell you about,” said Klose.

The congressman remained in

Washington only when he had to, spending the

rest of his time back in the district attending to a packed schedule of events;

his staff had to create specialized computer software just to keep track of where

he had to appear each day. The hardest position on Jontz’s staff was scheduler

because of his intense desire to be efficient with his time. Altman remembered

Jontz becoming “totally frustrated” on Mother’s Day because there was nothing

for him to do. “People used to joke . . . if there were two people together,

Jim Jontz would find them,” said Altman. For Sugar, who marveled that the

congressman had town meetings where there were no towns, one of the most memorable

experiences he had while working for Jontz occurred during an early morning

trip from Kokomo to Burket in

Kosciusko County to meet with

farmers in a local restaurant. “Those farmers could not believe it,” Sugar

said. “I’m sure they talked about that for the next two years—that Jim Jontz

walked in at five o’clock in the morning and had coffee with them and talked

about agriculture policy.”

The hard work and attention to detail paid off, as Jontz

twice won re-election. While in Congress he worked to make his mark on

legislation in a similar manner as he had while serving in the Indiana

legislature—through amendments, a procedure he used effectively on the 1990

Farm Bill. While other congressmen went home for the evening, Jontz stayed late

until the night, even making popcorn for hungry staffers from other

congressional offices as they worked to settle differences between House and

Senate versions of legislation. The staff members were not only “just floored”

that they got a snack, Buis noted, but there were also astonished that “it was

delivered and popped by a member of Congress. But Jim never thought of himself

as someone with a title above anyone else. That was part of his appeal to

people.” Klose noted that Jontz also made his mark in Congress by working within

the system to earn financial assistance for such projects back in his district

as the Hoosier Heartland Corridor road project, the psychological unit at the

Veteran’s Hospital in Marion, and Grissom Air Force Base near Peru.

Although Jontz attempted to find common ground with

Republican legislators, particularly on agricultural issues with GOP senator

Richard Lugar, he was not afraid to vote his conscience rather than what might

be popular back in his district, including voting against the use of force in

the Gulf War. “He didn’t care because he was doing the right thing,” said Campbell. “Look at the

political landscape these days and ask yourself how many people are doing

whatever it is they are doing, voting however it is they are voting, because

it’s the right thing to do. That’s a pretty small club.”

Jontz’s firm support of environmental issues frustrated and

sometimes enraged colleagues from across the aisle. His sponsorship of the

Ancient Forest Protection Act, which would have forbid cutting stands of

ancient timber in three western states, caused one Oregon congressman to call

him “a rank opportunist,” while another member of the Oregon delegation kicked

him out of his office in the middle of a heated argument. Angered by Jontz’s

successful push to end arrangements benefiting timber companies in the Tongass National Forest

in Alaska,

Congessman Don Young of that state introduced a bill to establish 35 percent of

Jontz’s district as a national forest. To answer charges that he was meddling

in matters outside of the district he represented, Jontz called the ancient

forests “a national treasure, much as the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and the

Everglades are. If we cut the last 10 percent of the ancient forests for

short-term greed, they will be gone forever. If we preserve them, future

generations, as well as our own, will be able to enjoy their benefits.”

Jontz’s life on the razor-edge of politics came to an end in

the 1992 election, when he was defeated by Republican challenger Steve Buyer.

Several issues hurt Jontz during that campaign, including an antipolitician

mood in the electorate inspired by the independent presidential candidacy of

businessman Ross Perot, opposition from western carpenter’s unions for Jontz’s

stand on old-growth forests, opposition from the pharmaceutical industry after

he held a town meeting to discuss the high cost of prescription drugs, and a

scandal involving the House bank involving a small number of overdrafts of

checks. “It was the death of a thousand cuts,” noted Sugar. Reflecting on the

first defeat ever in his political career, Jontz noted that he had been

“skating on thin” ice for a long time as a Democrat in mainly Republican

districts. “A lot of people didn’t think I was going to last more than one term

in the state legislature,” he told a reporter from the Indianapolis Star. “So I have been living on borrowed time for

years.”

Late on election night, when he knew he had been defeated,

Jontz asked Sugar to take him back to the Chrysler plant in Kokomo he had visited after he won his first

race for Congress. Early the next morning, Jontz was at the automotive factory gates

to thank the workers for their years of support, telling them it had been an

honor to serve them in Washington, D.C. Sugar remembered that some of the

workers refused to shake hands with Jontz, but, now liberated from seeking

their votes, the former congressman responded: “Oh, come on now, be a man,

shake my hand.” Sugar said he was proud of his boss “for not just rolling over

and taking it. He had given his life to their causes.”

In 1994 Jontz made his final try for political office,

losing a longshot attempt to unseat Lugar, a fellow Eagle Scout, who became the

longest serving U.S.

senator in the state’s history. Jontz lost in spite of a humorous television advertising

campaign that poked fun at Lugar’s interest in foreign affairs. The

advertisement had the former congressman jumping into his pickup truck after

learning that Lugar had secured $3 billion for Moscow. Jontz drove to

Moscow—Moscow, Indiana—to ask someone from the community about the money.

“Nope, haven’t seen a cent,” a woman in the advertisement told the candidate

while she stood under the Moscow town sign.

After his defeat, Jontz left

Indiana to battle on behalf of numerous progressive causes in an attempt to

forge coalitions among labor and environmental groups. He led an unsuccessful

campaign to stop the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement with

the Citizens Trade Campaign, served as president of the Americans for

Democratic Action, and worked as executive director for the Western Ancient

Forest Campaign. He participated in acts of civil disobedience, including

blocking a logging road in Oregon’s Siskiyou National

Forest in the spring of 1995. His parents were

aghast that he was arrested during the protest.

Jontz tried to mollify them by noting, “I had my suit on!”

Jontz moved to Portland, Oregon, in 1999, but Indiana still had a hold on him. He told his

mother that he sometimes thought of returning to the Hoosier State to buy a

plot of land in the Brown County hills, where he could sit back, relax, and

enjoy the trees. He never had that chance, dying at his home in Portland on April 14,

2007, after a two-year battle with colon cancer that had spread to his liver.

Visiting him during the former congressman’s final illness,

Sugar recalled walking into a Portland

hospital room to see Jontz on a conference call with fellow workers in the

environmental cause, offering them his ideas on what to do next. For Campbell, hearing about

Jontz’s death reminded him of campaign stop the two of them had made to one

house in a small town in the Fifth District. “I’ve never had a congressman come

to my door in the twenty-nine years that I’ve been an adult,” Campbell remembered the homeowner telling

Jontz. “When you live in some very small town like Royal Center, Indiana,

and not just you, but half the town says my congressman knocked on my door

today, that means something.”