A

series Martin did for the Saturday Evening Post on a government investigation of one of the country’s largest

and most powerful unions—the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen and Helpers of America, more commonly known as the

Teamsters—put him in the middle of a titanic battle between two men: a

determined (some said ruthless) investigator, Robert F. Kennedy, and a

rough-and-tumble union man, James R. Hoffa.

Journalists

had been investigating rumors that Teamster officials had been enriching

themselves at the expense of their members, and gangsters, salivating over the union’s

large pension fund ($250 million), had made inroads into its operations. During

the 1956 California presidential primary, when Martin had found himself

“swamped with too many speeches to write” for Stevenson, Pierre Salinger, a

former newspaper reporter for the San

Francisco Chronicle and then the West Coast correspondent for Collier’s magazine, offered his help.

According

to Martin, Salinger produced a few speech drafts, from which he used little,

but one day Salinger brought to Martin’s hotel room in San Francisco a Collier’s editor, who asked Martin to

research and write an article on the Teamsters (the union was not then under

investigation). “I told him I couldn’t undertake it till after the election; he

said he couldn’t wait; I suggested he get Pierre Salinger to do it, and he

did,” Martin recalled.

Salinger

jumped at the chance to write about such a powerful organization. As one

Teamster official told him, discussing the union’s firm grip on the country,

“When a woman takes a cab to the hospital to have a baby, the cab is driven by

a Teamster. When the baby grows old and dies, the hearse is driven by a

Teamster. And in between we supply him with a lot of groceries.”

Unfortunately

for Salinger, just when he finished his article, Collier’s went out of business. He had two job opportunities

waiting for him—one as public relations director for the Teamsters, and the

other as an investigator with a U.S. Senate subcommittee created on January 31,

1957, the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or ManagementField, which came to be widely known as the Rackets Committee. In addition to

the Teamsters, the committee investigated other unions as well as the growing

influence of the Mafia and the Chicago Syndicate.

Salinger

went to work in February 1957 for the committee, chaired by conservative

Democratic senator John L. McClellan of Arkansas, and shared what he had

learned about the Teamsters with its chief counsel, Robert F. Kennedy, the

younger brother of John Kennedy. Another journalist, Clark R. Mollenhoff, a

Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter for the Des

Moines Register, had for months been badgering Kennedy to probe the

Teamsters possible illegal activities.

Martin

had first become acquainted with Robert Kennedy during Stevenson’s 1956

presidential campaign, which Kennedy had joined to learn how to run such an organization

in anticipation of his brother seeking the Democratic nomination for president

in 1960. “He told me later he had learned how not to run one,” Martin noted. Robert Kennedy described the Stevenson

effort to a friend over drinks as a disaster and told Martin he had never seen

such a poorly run operation. “He should have seen 1952,” said Martin.

The

two men’s paths crossed again when Martin received word from his editors at the

Post that the magazine was interested

in a series of articles on the Rackets Committee’s more than two-year-long

investigation of the Teamsters and its top officials, including Dave Beck (convicted

of federal tax evasion charges in 1959) and James R. Hoffa (convicted of

bribing a grand juror in 1964, he disappeared from view in 1975, never to be

seen alive again). When the committee held public hearings, newspapers had

published “scrappy reports,” said Martin, but, as Rose pointed out, nobody had

yet been able to “put the whole story together,” and he suggested Martin take

on the task.

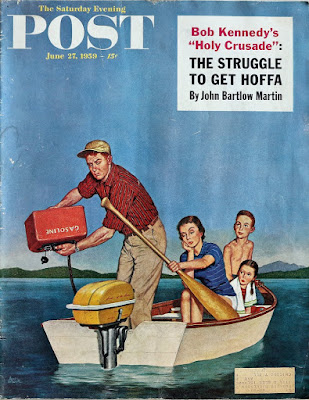

The

resulting seven-part series, published in the Post from June 27 to August 8, 1959, was Martin’s longest yet, taking

him nearly a year to put together, and setting a mileage record for his

legwork, as he traveled 17,000 miles around the country. In conducting his

research, Martin filled twenty 150-page notebooks and wrote a first draft that

ran 1,500 pages and 336,000 words; his final manuscript totaled 40,000 words.

Martin

had unearthed a remarkable study in power—the vast economic power wielded by

the Teamsters, with its more than 1.5 million members the largest labor union

in the world, versus the great political power wielded by the U.S. Senate. The

resulting investigation stood as one of the largest by a government entity

since the days of the Teapot Dome scandal of the President Warren G. Harding

administration of the 1920s and the banking and security fraud inquiries of the

1930s. “They exposed wrongdoings in big business; the McClellan committee alone

has gone after big labor,” said Martin.

The Rackets

Committee’s work (1,366 witnesses questioned produced a printed record of

testimony that ran to 20,000 pages) sent shockwaves through both political

parties, as well as the labor movement in America, and raised essential

questions still being argued about today—the use of and abuse of the Fifth

Amendment, the authority of Congress to investigate, the rights of individual

workingmen in a labor union, and the rights of an individual testifying before

Congress.

The

investigation also pitted the titanic personalities of two men, Robert Kennedy

and Hoffa, who became “bitter antagonists,” noted Martin. Hoffa viewed Kennedy

as a rich, “spoiled jerk,” while Kennedy’s determination to uncover the labor

leader’s criminal activity became “a holy crusade” to him, one of his friends

confided to Martin. Kennedy himself said the way Hoffa operated the Teamsters

meant it no longer served as a bona fide union: “As Mr. Hoffa operates it, this

is a conspiracy of evil.”

To

report on the investigation, Martin traveled to Washington, D.C., staying there

off and on for more than half a year and becoming a familiar presence at the

Rackets Committee’s offices in Room 101 at the Old Senate Office Building. For

his story he spent more time with Kennedy than with anyone else, sometimes

visiting with him all day in his private office and going with him at day’s end

to his home, Hickory Hill, in McLean, Virginia, for dinner—often a hair-raising

ride, as Kennedy, recalled Martin, “loved to drive his big convertible fast

from office to home, his hair flying.”

On

weekends at Hickory Hill Martin played, “not very well,” he admitted, the

traditional Kennedy family sport of touch football (at that time Kennedy and

his wife, Ethel, had six children), swam with Kennedy in his pool, and

accompanied him as he made trips around the country pursuing leads from

whistleblowers in the union. “I liked Bobby Kennedy from the start,” said

Martin. “Though born to wealth and power, he had about him not a trace of

superiority or affectation.”

Although dedicated to his work—Martin said he

“seemed almost obsessed”—Kennedy infused his office with a youthful,

lighthearted atmosphere. Martin remembered coming into Kennedy’s office and

seeing him and Kenneth O’Donnell, his administrative assistant, passing a

football back and forth as they discussed the investigation (the two men were

on the football team together at Harvard University). “He moved fast, handling

his body well, like an athlete,” Martin said of Kennedy. “He ran upstairs and

downstairs. He scheduled himself remorselessly, and he drove his staff just as

hard.”

Driving

Kennedy’s determination was the worry in the back of his mind that if the

investigation proved to be a flop, it might have a negative effect on his

brother’s political future, both his reelection to the U.S. Senate in 1958 and

his try for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960. “A lot of people

think he’s the Kennedy running the investigation,” Robert said of John, one of

the four Democratic senators who served on the Rackets Committee. “As far as

the public is concerned, one Kennedy is the same as another Kennedy.”

When

Robert Kennedy’s work took him to the Chicago area, he and some of his

investigators sometimes stayed with Martin at his home in Highland Park,

including one trip when Kennedy and his men were in the area to dig up a body

in a cornfield near Joliet, Illinois. Walter Sheridan, whom Martin considered

to be one of Kennedy’s best investigators, later indicated that Kennedy and his

staff had been looking for the body of a woman reporter from Joliet allegedly

killed for daring to expose labor racketeering in the city. They had been

tipped off by a convict in the prison there who said he knew where the body had

been buried; it turned out to be a bogus tip, but Kennedy and those with him

turned over a lot of earth in a farmer’s field before realizing “the prisoner

was just stringing them along,” Sheridan said. “They did a lot of digging.”)

As

Martin got deeper and deeper into his story, he discovered that there seemed to

be two different Robert Kennedys (a theme picked up on by many other

journalists during Kennedy’s subsequent career). There was the person few in

the public saw—the family man who went home to Hickory Hill and loved having

his children swarm over him when he opened the front door. Those who watched

the Rackets Committee’s hearing on national television, however, only witnessed

the relentless prosecutor, hectoring hostile witnesses who dodged his questions

on Fifth Amendment grounds, earning for Kennedy a reputation for ruthlessness

that dogged him until the end of his life.

Instead of seeing a coldblooded individual,

however, Martin thought of Kennedy as “hard driving, tenacious, aggressive,

[and] competitive”—a person who said his long and eventually unsuccessful

campaign with the Rackets Committee to put Hoffa behind bars was “a little like

1864, when [General Ulysses S.] Grant took over the Union Army to go back into

the wilderness—to go back slugging it out.” Unlike some of his friends who were

concerned about possible infringements of civil liberties, Martin did not

believe Kennedy persecuted Hoffa or denied him his constitutional rights. “As a

crime reporter, I had seen far worse prosecutions,” said Martin. “Indeed, I

thought he treated Hoffa fairly, on the whole.”

What

Martin could not understand was Kennedy’s conviction that the labor leader

represented America’s biggest problem—a notion that sounded odd to someone who

had only recently been involved in a presidential campaign concerned with helping

reign in the worldwide threat of nuclear destruction. Kennedy believed that if

someone did not do something about Hoffa’s damaging influence on the Teamsters,

gangsters would soon have a stranglehold on the country’s economy.

During the

investigation Kennedy had also grown to admire the rank-and-file members of the

Teamsters, and he believed that Hoffa had engaged in sweetheart contracts with

employers, receiving kickbacks in return and denying workers their fair due. Kennedy

also possessed, like some politicians Martin had known, an almost mystical

faith in the democratic system—a faith readers of the Post likely shared. “Like them [other politicians],” noted Martin,

“he links it with the righteousness of his own cause. He feels that, although

Hoffa may win a battle, he can never win the war, because justice and right

will prevail, owing to the excellence of this democratic system and the good

sense and decency of the American people.”

Martin

held a much harsher opinion of the investigators who worked for Kennedy. Most

of them were in their late twenties and early thirties and had previously

worked as newspapermen, FBI agents, or policemen. Kennedy had, at the inquiry’s

peak, forty-two investigators on his staff, aided by forty men from the

government’s General Accounting Office. “These men,” Martin noted in his

articles for the Post, “condemn

wrongdoing unequivocally. For many of them the crusade against Hoffa is their

first cause, important as first love. There is something a little chilling

about their moral certitude and zeal.” They lacked, Martin later reflected, the

tolerance for human weakness he had seen in the work of big-city detectives he

had known.

The

investigators’ ardor for justice did translate into meticulous evidence

gathering. Kennedy told Martin that for every witness called to testify before

the committee, twenty-five people had been interviewed and they examined tens

of thousands of documents for every one placed into the record. During one

inquiry, Salinger and two other investigators went through more than 600,000

checks from one company alone. Sheridan noted that as long as those on staff

did their work to the best of their abilities, they could always count on the

leader’s support—something he had not had in his previous job. “The big

difference—it was just a phenomenal difference to me—of going from the FBI to

work for Robert Kennedy was that with the FBI you knew that J. Edgar Hoover

would never back you up,” said Sheridan, “and with Robert Kennedy you knew that

he would. It was all the difference in the world.”

Kennedy’s

cooperation with Martin was part of the chief counsel’s ongoing effort to

cultivate good relations with the press, especially with columnists and

magazine writers. Edwin O. Guthman, a reporter with the Seattle Times who later became Kennedy’s press secretary at the

Justice Department, said that in his journalism career he had never encountered

someone in public life who had answered his questions “as candidly and

completely as he [Kennedy] did,” and he often briefed reporters in considerable

detail about the evidence to be presented at a committee hearing. Kennedy

developed “special relationships” with certain reporters, noted Guthman during

the investigation of Beck, and these writers always had access to him and

received tips on stories and verification of information when needed.

As a

reporter, Martin said it made him “a little nervous” to see journalists who had

completed independent investigations on the Teamsters, such as Mollenhoff,

exchanging information with Kennedy about what they had uncovered. In a draft

for his Post series Martin had

included a passage, cut from the published piece, pointing out that some

newspapermen had become so close to the investigation that they attended

committee staff parties almost like members of the staff themselves and some

shared their “zeal for getting Jimmy Hoffa.” As a representative of the Post, one of the country’s leading

magazines, Martin said he could count on Kennedy’s full cooperation, as he “was

anxious that the Post story come out

well; it was the first full-dress account that tried to pull the whole

investigation together.”

To

gain a broader perspective on the Teamsters investigation, Martin also talked

to some of the senators serving on the Rackets Committee, including McClellan

and the leading Republican member of the panel, Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona,

who he found to be “an amusing, engaging man.” Martin found himself spending a

lot of his time with John Kennedy, seeing him alone in his Senate office,

having breakfast with him at a New York hotel, and eating dinner with him and

his wife, Jacqueline, in Washington, D.C. When they were alone together, Martin

remembered that he and the Massachusetts senator “talked politics almost

entirely.” Kennedy had been gearing up to run for president in 1960 and the

primaries were about to begin in little more than a year. Although winning

primary races did not translate into a clear path to the nomination, they were

important to Kennedy as a way of showing to party leaders skeptical of his

youth and religion, as well as grassroot Democrats, that he could win support

from a broad spectrum of voters.

Knowing

of Martin’s experience in Stevenson’s two presidential efforts, Kennedy picked

his brain on what kind of campaign staff he might need, his opinion on various

issues, and how to connect with the academic world when it came to developing

policy ideas and position papers. “Jack Kennedy struck me as an extremely

attractive and extremely intelligent young man,” Martin said. “He presented a

lighthearted funny exterior, sometimes almost frivolous, but inwardly he was

deadly serious and he had an astonishing fund of information about all manner

of subjects, such as France’s problems in Algeria and the number of Nigerian

exchange students in the United States.” He also seemed, unlike Stevenson, to

“welcome challenges, not be burdened by them,” Martin noted. Many people Martin

ran into that spring and summer in Washington, D.C., including some former

Stevenson supporters, had begun to proselytize on Kennedy’s behalf. Martin still

had his doubts about Kennedy, as he was unsure if he was presidential material,

noting, “He was so young.”

For

the other part of his story for the Post,

Martin had to somehow convince a suspicious and hostile Hoffa to talk with him.

It would not be the first time in his journalism career that Martin had come up

against a recalcitrant Teamsters official. During his time as a young reporter

with the Indianapolis Times, Martin had

covered a truck strike and attempted to interview Daniel J. Tobin, then the

Teamsters president, at the union’s headquarters at 222 East Michigan Street in

Indianapolis (the union moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C., in 1953).

Martin remembered that Tobin’s office had a door that “was locked and

steel-barred, like a prison cell.” He had to stand in the corridor and shout

his questions at the union leader, who yelled his answers back to Martin,

usually responding with such curt statements as, “No,” “No comment,” or,

simply, “Go to hell.” No reporter, Martin ruefully noted, had ever “got much

out of the Teamsters.”

With

this experience behind him, Martin decided to use the prestige of his status as

a reporter with the Post, and the

possibility of finally telling his side of the story in an unbiased manner to

the American people, to convince Hoffa to open up to him about his life and

work. He adopted the stratagem of calling Hoffa not from his home, but from the

Post’s Chicago advertising office,

having the switchboard operator place the call, and leaving the Post’s telephone number for Hoffa to call back. “Moreover,” said Martin, “this kept

my home telephone number, and hence my address, out of Teamsters headquarters,

which seemed only prudent in view of the reputation of Hoffa’s associates.” The

strategy worked; after a week of telephone calls, Hoffa finally called Martin

back and agreed to an interview at Teamsters headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Ushered

into Hoffa’s plush office, Martin spent two hours interviewing the Teamsters

president, mindful that their talk was probably being recorded. He was able to

convince Hoffa that he wanted to hear his point of view on the union

controversy, and Hoffa agreed to tell other union officials to talk to Martin

and allowed the reporter to follow him as he did his job, including negotiating

contracts with Midwest truckers in Chicago and accompanying him on a flight

from Chicago to Miami for the Teamsters’ annual meeting. Martin, who refused to

accept an airline ticket bought for him by Hoffa (Martin had anticipated such a

move and had bought his own), sat by him for the entire flight, and the two men

talked all night with few interruptions, except for one by a stewardess who

recognized Hoffa, “which secretly pleased him,” noted Martin.

Instead

of asking questions about the investigation, which he knew Hoffa would either

be unresponsive about or refuse to answer, Martin concentrated on details about

the union leader’s life and his views about the U.S. labor movement. “I liked

him,” he said of Hoffa, perhaps because the two men viewed themselves as fighting

for the underdog. At one point in his life Hoffa had been arrested eighteen

times in one day for his union activities, but he persevered to become

president of Teamsters Local 299 in Detroit. The local served as his power base

as he clawed his way to the union presidency using, along the way, often brutal

tactics and counting on allies who had no qualms about using force to get their

way. “I’m no damn angel,” Hoffa said.

As

Martin insightfully pointed out in his Post

series, the image of Hoffa as “the cocky little underdog battling the

United States Government is not false; it is his natural role.” In fact, he

went on to write, if Robert Kennedy of the Rackets Committee had not existed,

Hoffa “would have had to invent him.” A man without hobbies who neither smoked

nor drank, Hoffa, a devoted family man, concentrated all his efforts on behalf

of the Teamsters, working to gain its members better working conditions and

more money. “Running a union is just like running a business,” Hoffa told

Martin. “We’re in the business of selling labor. We’re going to get the best

price we can.”

In

evaluating the Rackets Committee’s investigation of the Teamsters, Martin reported

that it produced a demand for reform legislation to stem in part the influence

of racketeers in the labor movement, and he also had an overall good opinion of

the work done by Robert Kennedy and his staff. “There was remarkably little

politics in the committee’s work,” Martin wrote. “McClellan stood firm against

pressure and made no mistakes. Indeed, had all congressional committees

conducted themselves so well, congressional committees would have received less

criticism in recent years.” But the federal investigators had failed in one

task—Hoffa remained Teamsters president and had been acquitted in the two

criminal trials resulting from the committee’s work.

In

his time with both Kennedy and Hoffa, Martin also discovered that the two

fearsome antagonists shared similar qualities, as they were both “aggressive,

competitive, hard-driving, authoritarian, suspicious, temperate, at times

congenial and at others curt.” They were also physical men who sought to keep

in shape, often by doing push-ups, and in spite of their wealth and power

“eschewed frivolity or indulgence and both seemed oblivious of their

surroundings. Both were serious men and, in their own ways, dedicated,” Martin

later observed. As for their opinions on the long investigation, Martin wrote

that Hoffa shrugged off the committee’s relentless focus on his union, saying,

“You just put in your time. And when they get tired of kicking us around

they’ll adjourn and forget about it.” Kennedy admitted to the writer, “It’s

been a real struggle.”

When

he had finished his story, Martin offered to show his manuscript to both Hoffa

and Kennedy so they could correct any factual errors, but not his

interpretations of events. Although Hoffa turned down Martin’s offer, Kennedy

spent the better part of a day and well into the night going over the manuscript

point by point with Martin at the writer’s hotel room in New York. It proved to

be “not an easy negotiation,” said Martin, as Kennedy was as tenacious with the

reporter as he had been with reluctant witnesses appearing before the Rackets

Committee. “What bothered him the most about the MS [manuscript], I think, were

the similarities I noted in the piece between him and Hoffa,” said Martin. “He

was amazed and simply could not understand; it had never occurred to him; he

had thought of himself as good and Hoffa as evil; I was looking at them from a

different angle.”

Once

during their discussion Kennedy asked Martin why he had not included statements

that could be damaging to Hoffa. “I asked if he could prove them by sworn

testimony,” Martin noted. “He said he could not but he knew they were true, he

couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t put them in.” The reason Martin was so

cautious of course was because of the possibility of a damaging libel action

against the Post by Hoffa and the

Teamsters. As a lawyer himself, Kennedy should have known this, but Martin put

this misunderstanding down to the chief counsel’s youth.

The

sometimes contentious back and forth between Kennedy and Martin on the Hoffa

story did not diminish Martin’s respect for the investigator, or Kennedy’s esteem

for the reporter. Years later, Martin reflected that no matter how much Kennedy

viewed Hoffa “as evil and himself as good, he never once objected to my

attempts at impartiality. Nor did he ever let those attempts impair our own

personal relationship.”