Walking

down from the mountain, the man in the American uniform could hear the scream

of something sinister headed his way. Months of previous combat experience

caused him to instinctively dive to the rocky ground for safety. It was too

late. He felt a “smothering explosion” engulf him. In the fraction of the

second before unconsciousness came, he knew that he had been hit by a German

shell.

He sensed

a “curtain of fire” rise, hesitate, and hover for “an infinite second.” An

orange mist, like a tropical sunrise, arose and quickly set, leaving him, with

the curtain descending, gently, in the dark.

Unconsciousness

came and went in seconds. When he awoke, he knew that he had been badly

wounded. In that moment he realized something he had long suspected—there was

no sensation of pain, only a “movie without sound.” Still stretched out on the

rocky ground of Mount Corno in the Italian countryside, he could see, a couple

of feet from him, his helmet, which had been gouged in two places—one hole at

the front and the second ripped through the side. Catastrophe. How could he

mange to make it to safety, nearly a mile away down the trail, where the

officers that had accompanied him earlier on the mountain, Colonel Bill Yarborough

and Captain Edmund Tomasik, he hoped, were waiting?

It was

eerily quiet, as if time stood still. He could still move a bit. He sat up and

saw figures of crouched men he did not recognize running up the trail. He tried

to yell at them but found that his voice produced only unintelligible noise

instead of words. Although rattled at first, he became calmer when he realized

he could still think—he had lost his power of speech, but not his power to

“understand or generate thought.”

Another

shell came screaming down. He hugged the ground and braced for the imminent

explosion. When it came, he found it was a “tinny echo” of what had before been

powerful and terrifying. A frightened soldier skidded into his position to

escape the danger, and he tried to talk to the man, seeking his help, but only

produced the strangled question: “Can help?” As another shell burst farther

down the mountain slope, the soldier, with terror etched across his face, could

only say, before he ran away, “I can’t help you, I’m too scared.”

In a haze,

he barely remembered the medic who flopped beside him, bandaged his wounded

head, and jammed a shot of morphine into his arm. Almost as soon as he had

appeared, the medic was gone, and again he was alone. He realized that if he

wanted to ever get off that mountain, he had to get up and walk.

Almost

miraculously, he found his glasses, unbroken, lying on the rocks a few inches

away. He tried to pick them up with his right hand, and realized his entire

right arm was stiff and useless. Using his left hand, he picked up his glasses,

put them on, and, almost, absentmindedly, placed his helmet on his bandaged

head, where it sat, a fine, if precariously balanced, souvenir.

As he

staggered down the mountain, he kept dropping and picking up his helmet, and

came under fire from a procession of shells. Once a shell burst so close to him

that he could have touched it. He was not frightened, but only startled at its

nearness.

Finally,

he wedged his tall, lanky frame into a small cave to wait out the barrage. He

remembered being unconcerned about his plight; nothing seemed to disturb him.

In fact, it seemed somehow that after escaping so many close calls during the

war, his luck would finally run out. Only his instinct for self-preservation

told him what to do. Despite the blood running copiously down his face,

blurring his vision, he got up and staggered down the mountain like a robot,

unsteady on his feet but under some directional control.

Rounding a

bend in the trail, he saw Yarborough and Tomasik trying to help a wounded

enlisted man. A surge of pleasure surged through him as he realized he would be

saved. The colonel started to wave to him, then stopped, noticing his bloody

glasses and blood-soaked shirt. With Yarborough’s help, he made it to a house

to await transportation for medical assistance.

The

wounded man, Richard Tregaskis, a correspondent with the International News

Service, looked across the room and saw a line of soldiers, with “fascinated,

awed looks on their faces as they stared at me, the badly wounded man.” Those

spectators, he noted, imagined more pain than he felt. “Such is the friendly

power of shock,” Tregaskis remembered, “and the stubborn will for

preservation.” Reflecting on his experience, he felt almost a sense of relief that

at last it had happened—he had been hit. He felt sure he was supposed to die,

but he did not.

Finally

transported to the Thirty-Eighth Evacuation Hospital, Tregaskis underwent

several hours of brain surgery performed by Major William R. Pitts. A shell

fragment had driven ten to twelve bone fragments into Tregaskis’s brain and

part of his skull had been blown away, with the brain, said Pitts, “oozing out

through the scalp wound.”

Recuperating,

Tregaskis received a visit from one of the biggest stars of journalism in World

War II, Ernie Pyle, columnist for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. After

chatting with his colleague, Pyle wrote in his popular column that if he had

been injured as Tregaskis had been, he would have “gone home and rested on my laurels

forever.”

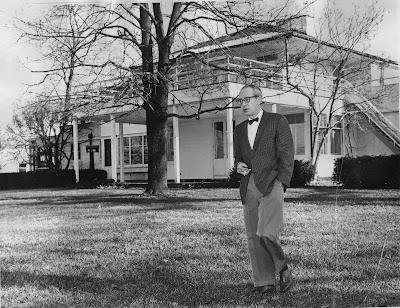

Tregaskis

did go back to the United States—to the U.S. Army’s Walter Reed Hospital in

Washington, DC, where doctors put an inert metal (tantalum) plate to cover the

hole in his skull. It seemed an end to what had been a brilliant wartime career

that included witnessing the Doolittle Raiders take off from the pitching deck

of an aircraft carrier to bomb Japan, being in the thick of the action during

the Battle of Midway, surviving seven nerve-wracking weeks with U.S. Marines on

Guadalcanal, writing a best-selling book about his experiences (Guadalcanal Diary), and accompanying

American and British troops for the invasions of Sicily and Italy.

Asked by

the editors of a national magazine to return to the Pacific to follow the crew

of a B-29 Superfortress as it prepared for bombing missions against Japanese

cities, Tregaskis was asked by an editor, “Do you really want to go?” Without

hesitating, Tregaskis gave an answer that any reporter who covered World War II

would understand: “I don’t want to go, but I think I ought to go.” He went.

.jpg)