Situated on the Janiculum Hill, the American Academy in Rome has, since its establishment in 1894, been home to visiting scholars and artists from the United States seeking support and inspiration for their work. During the heady days of Rome’s liberation during World War II, one of the academy’s former students, Harry A. Davis Jr., a sergeant in the U.S. Army, made his way to what had been his art studio at the academy just a few years before.

Davis discovered that everything was just as he had left it, including his paintings and personal effects. He also found that his worst fears about the colleagues he had left behind had not come to pass. Although showing “distinct signs of having suffered from a lack of food,” his friends at the school “were all alive, happy to see Americans again.” With his company bivouacked on the grounds of a nearby estate, the sergeant was able to make several trips to the academy, “each time taking some of my ration of candy, for they had no sweets for several years,” in addition to other supplies.

A graduate of Indianapolis’s John Herron Art School, Davis, from Brownsburg, Indiana, had experienced numerous travails since being honored in 1938 with the multiyear Prix de Rome fellowship for a series of his paintings, including one titled Harvest Dinner, which depicted a large rural family gathered for a meal. The outbreak of another war in Europe had interrupted Davis’s studies and, with his country’s entry into the conflict, he had used his artistic talents to cleverly disguise U.S. military installations and equipment from the enemy through his service with the Eighty-Fourth Engineer Camouflage Battalion. Davis’s arrival in Rome not only brought him back to his student days, but it also altered his wartime career.

Davis was able to wrangle a transfer as a combat artist with the Eighty-Fifth InfantryDivision, working under the supervision of the U.S. Fifth Army’s Historical Section, led by Chester Starr, his friend from his time at the academy. “I was to go along with the Division as they were on the move and while they were at rest, my job was to tell the story, to the best of my ability, of the life of the front-line infantryman, in and out of battle,” Davis recalled. The paintings and drawings produced by Davis and the other combat artists with the Historical Section were later used to help illustrate a nine-volume history of the Fifth Army, and some of his pieces were displayed at the White House.

Upon his return to Indiana at the war’s end, Davis had a successful teaching career as a professor of painting and drawing at Herron for more than thirty years. He also continued to paint, producing more than 500 pieces, many featuring endangered historic buildings in the state. “Most of the work is because I feel a need for it,” Davis said. “Somebody ought to record it. The old landmarks are disappearing so fast.”

Reflecting on his World War II service, he noted that the conflict provided an almost endless amount of material to record, including scenes of violence and bloodshed that he sometimes found hard to stomach. “Torn and crumbling buildings, dead dismembered bodies of soldiers, both our own and the enemies, and rugged and treacherous mountain passes, that were scarred and pitted with shell holes,” Davis wrote in his memoirs about his wartime experiences. He did find time to record on canvas quieter scenes behind the front lines, including American soldiers interacting with Italian families grateful for their liberation.

Edward Reep, the officer who oversaw the combat artists assigned to the Historical Section, praised Davis for jumping into the thick of the fighting and establishing himself as “a very significant, intrepid member of the unit.” Reep noted that the Hoosier artist involved himself in “gut-level ground warfare” at great personal risk,” and skillfully incorporated soldiers of the Fifth Army as the primary subject matter in his work.

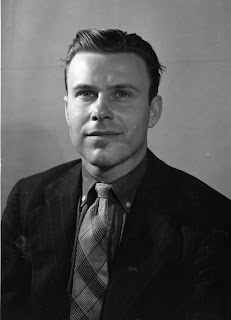

Earning a precarious living as an itinerant minister, Harry Davis Sr. remembered that his namesake, Harry Davis Jr., born on May 21, 1914, possessed an early aptitude for art. “Ever since he was old enough to hold a pencil,” the senior Davis told a reporter, “he has been drawing likenesses of people.” Although local schools offered neither art nor manual training courses, Davis Sr. noted that his son filled their house with “model stage coaches, airplanes, and boats of beautiful craftsmanship which he did just to satisfy the creative urge and to amuse himself.”

In 1933 the junior Davis entered the Herron School of Art at 1701 North Pennsylvania Street in Indianapolis, supporting his education by winning several scholarships. He began his training at Herron during a time of great changes at the institution under the leadership of the school’s new director, Donald Mattison, a New York artist and teacher. Mattison took on his duties the same year Davis started his studies.

Faced with budget troubles and a declining enrollment, Mattison trimmed the Herron faculty and altered the school’s curriculum so that during their first three years students followed a similar course of study with an emphasis on a firm grounding in drawing, composition, and painting. During their fourth year, students could pick a specialization, including painting, sculpture, commercial art, or teaching. Promising students were able to win scholarships for a fifth year of postgraduate training. “The art school must become the clearinghouse wherein those found unfit for professional work are eliminated,” Mattison observed. “Cold facts, as to proficiency must be recorded and ranked by percentages. Authoritative recognition of the true professional student must exist and adequate instruction must be provided for the deserving students.”

In addition to balancing Herron’s budget, Mattison also inspired his students to aspire to win the art world’s two top honors—the Prix de Rome, which Mattison had won in 1928, and the Charloner Paris Prize. Herron students answered the director’s challenge with gusto. Davis’s 1938 Prix de Rome, which included a stipend and allowance for travel amounting to approximately $1,400 a year, followed one awarded to Clifford Jones in 1937. Sculptor Robert Pippinger captured the prize in 1939, joining Davis at the academy, and Loren Fisher won it in the next year. Davis first learned of his award when fellow Herron students tracked him down while he was relaxing, sunbathing along the Central Canal near Butler University. “I had no expectation of winning,” Davis said to the Indianapolis Star when his prize was announced, “although many people had praised the realism of my picture.”

During his time in Rome, Davis worked on a variety of projects, including a fresco he titled The Sacking of Rome by Alaric, grouping eighteen life-size figures in a setting of an ancient Greek temple. He spent five weeks on the painting, as well as doing drawings and easel paintings in his studio space. Accompanied by other students he also had time to take several trips through Italy, studying the work of old masters in various museums, galleries, palaces, and private homes. “After each period of travel I would go back to the studio and experiment with the technique of old masters,” he remembered.

Later, Davis did a six-week tour of Greece with another fellow at the academy, Starr, who was studying history. Davis wrote to Mattison that he had grown “tired of going through galleries and seeing art all the time. I wanted to see people and life.” By traveling with Starr, Davis hoped to see “Greece from the point of view of an ancient historian,” and, through his own eyes as a painter, experience the country’s “people, customs, etc.”

Davis also took trips to Turkey, France, and Egypt, a country he particularly enjoyed. “I think people are right when they say it gets under your skin to see this country,” he wrote Mattison in February 1940 about his time in Egypt, which included a stop at the Valley of the Kings on the Nile River’s west bank near Luxor. “I never saw such beauty of workmanship ever.”

In April 1940 Davis learned that the academy had decided to extend his fellowship from two to three years, an offer the Hoosier student accepted. He explained to Mattison that for the past several months he had “found my stride, you might say and now I am painting hard and really am getting someplace. So I’m thinking that I can keep that up next year if I stay then I will be able to have a good deal of work to make a showing.” He and Pippinger had become close, with the sculptor offering Davis “some good constructive criticism” and the two engaging in long, instructive discussions about art. An admirer of Pippinger’s work, Davis noted that the two Herron graduates had “quite a bit in common,” writing Mattison that they were both “interested in accomplishing something and are quite serious about it and we can give one another good suggestions.”

Unfortunately for Davis, the political tensions in Europe had already erupted into war following Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939. By the spring of 1940 the war had made its mark on the academy and its students. “We never know these days what the tomorrows will bring,” Davis explained in a letter to Mattison. “Right now it is hard to concentrate on what you are trying to do and one is almost afraid to start on anything for fear he will not get it finished.” With Nazi Germany’s invasion of France in May 1940, Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, after a period of nonbelligerency, declared war on Great Britain and France on June 10. Joined by Pippinger, Davis left Rome for Naples, where the duo was scheduled to sail home on June 28 aboard the Excalibur, the last American ship out of the Mediterranean.

Davis and Pippinger arrived in Naples a week before their ship left port. While in the city, they witnessed several air raids made by British bombers. They saw Italian women run in the streets and run up to the two foreigners with such questions as, “Why don’t they stop the war?” and “Will America be on our side?” The artists also had to endure some tough questioning from local police, who grew suspicious of them after seeing them sketching, believing they were spies making maps of the Italian defenses. According to Davis, many of the passengers on the Excalibur were employees of oil companies stationed in Egypt and Palestine. “These oil men were bringing their families back to America,” he recalled. “And their families included numerous small children who insisted on getting up at 4 o’clock in the morning. From that time on, their noise added to the discomfort of sleeping in cots placed close together on the floor.”

Upon returning to the United States Davis spent studied art in New York as part of his fellowship before accepting, in 1941, a position as artist-in-residence at Beloit College in Beloit, Wisconsin. With America’s entry into the war following the Japanese attack on the U.S. Fleet at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands on December 7, 1941, Davis enlisted on October 10, 1942, receiving his basic training at Camp Livingston in Louisiana.

Army life proved to be quite different from what he had known as a civilian. Assigned to the Eighty-Fourth Engineer Camouflage Battalion, Davis discovered that not enough soldiers “with ability” could be found to bring the unit to its required strength and, therefore, “men, some of them unable to read and write, and all of them not wanted by other outfits, were used to fill the vacancy.” Davis decided that he might as well “try to get along with these guys and make the best of the situation” as the unit sailed for action overseas in 1943 onboard a flat-bottomed Landing Ship, Tank. “It’s no fun to be headed out where you can see nothing but water clear to the horizon,” he remembered, “and not have the slightest idea what your destination is.”

After a thirty-one-day voyage, the LST carrying the men of the Eighty-Fourth docked at Arzew, a port city in French Morocco near Oran in North Africa. German general Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps was being pushed out of North Africa by American and British troops, so Davis and his unit had some breathing space before seeing action. Its mission was to use concealment and deception to help safeguard American offensive operations, as well as, the U.S. Field Manual outlined, “to surprise, to mislead the enemy, and to prevent him from inflicting damage upon us.”

For its first assignment, the Eighty-Fourth traveled to an airfield in Tunisia (probably Hergla Airfield) to work with the pilots of the Twelfth Bombardment Group to disguise its squadron of North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers. “Besides camouflaging the planes by the use of broken shapes and flat colors,” Davis noted, “our work was to make their entire layout less conspicuous.” The pilots made sure to caution the men of the Eighty-Fourth to make sure they did not cover up the bomb markings painted on their planes that indicated successful missions flown. When they discovered Davis’s artistic ability, the fliers kept him busy the rest of the time he was at the airfield painting nose art on their bombers, usually scantily-clad women or popular cartoon characters. “The airmen thought that was really fine art, and they were happy, and I think they were given a little more courage by our work for them,” Davis observed.

For the rest of the time the Eighty-Fourth stayed in North Africa, the unit used its skills to work on the equipment carried into battle by the Eighty-Second AirborneDivision in preparation for the unit’s parachute jump for the invasion of Sicily. Davis and the Eighty-Fourth also helped construct decoy installations at points along the coast of North Africa from Oran to Tunis and inland toward the desert “to deceive the enemy as to the movement of our supply line. Along the coast we constructed dummy ships, and inland it was supply depots that we imitated.” The work left Davis exhausted at the end of the day, leaving him too tired to do any of his own work except for a few sketches of the local population and Algeria’s luxuriant green hillsides.

Davis learned in December 1943 that the battalion was supposed to join the U.S. Fifth Army, which had been battling German forces in Italy since September. “I was glad that we would not spend the whole winter in Africa,” Davis recalled, “for I wanted to get to Italy, and to more familiar places, but I didn’t know how I would feel, coming back to a place in which I had some pleasant times, and find utter destruction.”

The journey to Davis’s old haunts proved to be a tortuous one, taking twenty-seven days for a trip that normally should have taken only three or four days. A storm battered the Liberty ship transporting the Eighty-Fourth from Oran to Naples. Tanks and trucks nestled in the cargo ship’s hold broke loose from their restraints and slid “from one side of the ship to the other,” Davis noted, bashing into the sides with such fury that he believed the vessel might sink.

Finally disembarking at Naples on January 25, 1944, landing on the same pier that he had nearly six years before, Davis heard a rumor that his outfit would be transformed into a combat engineer battalion and sent to the front to build roads. He also discovered that Naples had been enduring nightly bombings by German planes. “The city was teeming with people, tired, dirty, and beaten down, who seemed to be wandering around, without any destination, or purpose,” Davis recalled. “Wounded women and children, many of them with bandaged heads, arms, and limbs, people crippled, and maimed, with eyes that burned of misery and fear, were the kind of sights that first greeted my eyes.”

Luckily for the Eighty-Fourth, the rumor about its transformation into a road-construction crew turned out to be false, and its men were quartered in the ruins of a castle on a hill in a place named Vairano Patenora that overlooked the Volturno River valley. The countryside seemed peaceful during the day when Davis could hear only an occasional shell falling. “But at night, when things let loose, one couldn’t forget there was a war going on,” he noted.

With his new duties as company draftsman taking less of his time, Davis found time to explore his surroundings, occasionally striking up a conversation with Italian laborers and farmers venturing out in the improved spring weather. During one of these trips, he came upon several peasant women working in a field of new wheat—a scene that inspired him to produce a painting titled Tillers of the Grain. Doing the painting provided him “a wonderful relief, a mental rest, an interruption” that greatly improved his morale and reminded him of “Italy’s real self midst chaos.” In a letter home discussing the work, he outlined some of the difficulties he faced in its production, which took three weeks:

I have had to employ a different and almost corresponding unorthodox way of painting. My easel was at times a chair, while again, a tripod arrangement upon which the canvas was hung. At no time was I able to get suitable lighting conditions, working in a tent, sitting on my cot. The canvas for my painting was originally shielding some soldier from the elements, a salvaged shelter half, a half-section of the small pup-tents. It was stretched over a frame made of tent stakes. The sizing and ground to paint upon was white camouflage emulsion. This I used as white pigment, as well, for the oil set that I accumulated did not contain white. Six colors were all that I could gather, with two brushes and a palette knife. I used linseed oil that had been thickened by setting in the sun until it became rich in consistency. Vibrations in the air were strong enough that the canvas quivered like a drum struck with a heavy blow.

In May 1944 the Eighty-Fourth found itself on the move again as American forces raced to break through the Gustav Line and reach Rome, finally liberating the city on June 4, 1944. Davis and his unit moved nearly constantly, staying only a day or two in one spot before moving on to the next, doing a variety of camouflage jobs. “All along the way, familiar places and names of towns would loom up, for along this highway I had been many times, before the war, but now, towns and cities were flattened,” he remembered.

Relieved at finding the academy safe and undamaged, Davis had another pleasant surprise when, during a visit, the academy’s superintendent of grounds told him that another former student, Starr, had visited and left his address behind. The two men met, and although Starr had risen to officer status with the Fifth Army’s Historical Section, and Davis remained an enlisted man, because of their previous friendship “we met, not as a Lt. Col. [lieutenant colonel] and a Sargent [sic], for the military courtesy seemed out of place at such a meeting.” Davis told Starr about his previous work with the Eighty-Fourth, adding that he now wanted a “chance to paint, instead of the designing I had been doing.”

Starr set out to fulfill his friend’s wishes. As he told Davis in a late June 1944 letter, however, he could not secure for him a transfer directly to the Historical Section. Starr explained that each division in the Fifth Army had an artist on its staff, either a commissioned officer or an enlisted man. These soldiers were then placed on detached service with the Historical Section. “This policy insures that the artists work on the most promising subjects, that they are under centralized direction,” Starr wrote, “and that they have full access to all artistic materials in the area of that division, painting the terrain of its major sections, sketching typical members of its units at work in the field, and in general putting in visual form a record of its activities.”

Once an artist submitted his work, Starr added that the Historical Section sent the art to the U.S. War Department as a permanent part of the division’s history. Some of the pieces were also put on public exhibition. Luckily for Davis, an artist slot was available for both the Eighty-Fifth and Eighty-Eighth Infantry Divisions. In August 1944 Davis received orders to report on detached service to the Eighty-Fifth Division’s headquarters company, reporting there in September in time for its push north of Florence.

Davis viewed his assignment as accompanying the division as it was on the move, engaged in battle, and at rest. The uncertainty of warfare meant that Davis had to make quick sketches under trying conditions. Often, he could not return to the same spot to sketch and, if that was possible, the object or objects in the sketch—either buildings or people—would be altered “or might very well not be there at all.” Just a taste of what life was like for the average infantryman made him thankful that he did have to endure combat for months on end.

After spending time with the division, Davis returned to the Historical Section to produce his paintings, working under more favorable surroundings and with access to art materials, allowing him to work in pen and ink, watercolor, gauche, and oil. “On our finished work, we were to take as long as we desired,” he remembered, “not having to meet a deadline. The finished work would be photographed, we would receive some prints and the negative for each piece of work, and then our work would become the property of the War Department.”

From October 1944 to April 1945 the Fifth Army had its headquarters in a former tobacco and cigarette factory in Florence. Reep recalled that the factory turned out to be “a pleasant and convenient accommodation, for it was located near the heart of a magnificent city brimming with unrivaled architectural jewels . . . a stone’s throw from the ancient and fabled Pontevecchio,” the ancient stone bridge spanning the Arno River and noted for the shops built along it. Davis had time to explore the city, viewing the old frescos made by Massaceio, Giotto, Benozzo, Gozzoli, and Ghirlandaio, as well as the sculptures of Donatello and Michelangelo.

For the winter months, Davis's work concentrated on capturing the dugouts and huts infantrymen constructed to give them some shelter from the elements. While GIs of the Eighty-Fifth were out of the line and resting, with five-day passes in hand, Davis produced sketches of them interacting with families, bargaining with local merchants, having their laundry done, and trying to make themselves understood using their rudimentary knowledge of the Italian language.

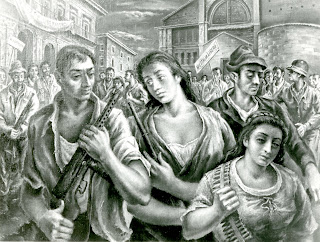

Davis had trouble keeping up with the Eighty-Fifth in the spring of 1945 as the division renewed its drive on Bologna and the Po Valley. Shortly after Bologna had been taken by Allied forces, Davis visited the city and came upon Italian partisans, “little bands of men and women of all ages, equipped with weapons of every description, who fought gallantly to rid their country of Fascism.” Their activities, and the colorful celebration after Bologna’s liberation, inspired him to produce a painting featuring the partisans. By early May, with German troops surrendering by the thousands, Davis worked sketching the captured enemy and their equipment as they were herded into prisoner of war camps “packed to overflowing.”

By May 17 the artists of the Fifth Historical Section had moved their operations to the Palazzo Martinengo Caesaresco, a magnificent palace constructed in the sixteenth century and situated on the shores of Lake Garda. “As I remember those days, it seemed like we were having a vacation,” Davis recalled. Reep noted that after spending a few years in “bedrolls and sleeping bags, army cots and foxholes, insects, worms, dirt, and shellfire, I thought for sure I was in heaven.” The palace provided soft, comfortable beds; maid service; hot and cold running water; and three hot meals a day served in a clean mess hall. The spacious grounds, Reep recalled, also provided plenty of room for such recreational activities as croquet, tennis, softball, and volleyball.

In this serene setting in northern Italy, the artists were able to produce “stirring work,” said Reep, with some “ideas that had burned into their minds during the conflict had been impossible to do justice to while constantly scrambling about and working in crudely erected tents.” Davis had time to work on two oil paintings, spending more time to finish them than he had on his other works. In addition, he noted that the artists had many ideas and sketches that had never been “worked up into paintings, but we had decided that we were going to try to carry our drawings and paintings beyond the stage of sketches.” They had seen plenty of war art that looked as if it had been done in foxholes, but instead had been done in a studio, he noted, “with a lot of quick strokes and spots, to give one the impression of it having been created in the fury of battle. That was not our purpose.” Instead, Davis viewed what he and his fellow combat artists were doing with the eyes of another profession—a historian: “We saw things as they were and we put them down, very much as a Historian would record the events that occurred. Some of my drawings had to be very factual and maybe they are not art but I feel they tell the story.”

Mustered out of the service on November 23, 1945, Davis returned to Indiana, earning a faculty position at Herron, where he remained until his retirement in 1983. A former colleague praised him as knowing how to “get the best out of his students. He wasn’t a soft touch. He wasn’t easy. Art was his life.” In 1948 Davis married Lois Peterson, a fifth-year student at Herron. “We quickly became good friends,” Lois remembered, “but I didn’t take any of his classes. He likes his students neat and dislikes walking into someone’s palette and getting paint on himself. If I had been in his class that might have happened because I’m a messy painter.”

For a time in the 1950s, the couple lived in Brownsburg and Davis, uncertain about his art and the market for it in Indianapolis, decided to supplement his teaching income by building houses. He abandoned that trade, but it left him with a strong understanding of how such structures are put together, using that knowledge to capture on canvas the state’s historic urban architecture, trying to find structures that possessed a wide range of shapes and the correct combination of lightness and darkness.

Davis likened his paintings of buildings to capturing a portrait of a man. “As in the face of a man, the features of a building are enhanced, the forms strengthened and given depth by proper lighting,” he told a reporter. As in the portrait of an older person, the “lines and blemishes that come with age add character to the countenance. Some structures are more handsome than others merely because of the arrangement of shapes, just as in a human face. The weathering of many a storm, and survival against the elements, can add greatly to the fascination of an old building.”

Until his death at age ninety-one on February 9, 2006, Davis and Lois produced art, working out of separate studio spaces in their two-story, shingle home on North Washington Boulevard in Indianapolis’s Warfleigh neighborhood; Davis converted the garage into his workspace, while Lois did her painting for a time in a basement studio, later moving to an upstairs bedroom. “We comment a lot on each other’s work,” noted Lois. “He will tell me what is wrong with my painting or if he looks at it and doesn’t say anything then I know it just isn’t right. He’s very careful about what he says. He will ask me for help and quite often I can pinpoint something and help him too.”

Davis was meticulous about his paintings, taking photographs of the building beforehand and making detailed sketches of the work to come. It took him anywhere from a few days to several weeks to finish a painting. When he finished, he took photographs of the completed work, as well as making sure to keep careful records of where it was exhibited, any prizes it won, and to whom it was sold.

Talking with a reporter about his work, Davis noted that some in the art world believed he underpriced his paintings. “Maybe I do,” Davis agreed, “but a large part of the satisfaction to an artist is not the price, but the knowledge that other people are able to see his work.” He also believed that artists should never retire but must paint “until they are unable to lift a brush, seeing and gathering more and more ideas to include in their work.”