On July 14, 1965, Adlai Stevenson II, two-time Democratic presidential candidate and diplomat, was in

London following a speech in Geneva, Switzerland. During his stay, Stevenson

had met with British prime minister Harold Wilson and visited friends. That day

after lunch he and Marietta Peabody Tree, his confidante and lover, went for a

walk in Grosvenor Square near the U.S. Embassy as he wanted to show her the

house he had lived in with his family while working on the UN Preparatory

Commission following World War II. The house, however, had been torn down and

replaced with a modern building, which caused Stevenson to sigh and comment,

“That makes me feel old.”

The duo walked on toward Hyde Park, but Stevenson asked Tree to slow down before uttering his final words, “I am going to faint.” He fell over backward, hitting his head on the pavement, unconscious. Although passerbys, including a heart doctor, tried to help, and an ambulance arrived to take him to the hospital, Stevenson died, the victim of a massive heart attack.

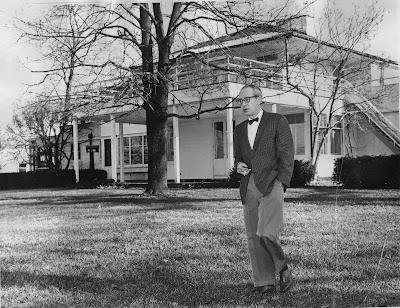

The news about Stevenson’s death reached John Bartlow Martin, who had worked as a speechwriter in his 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns, while he and his family were vacationing in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. That night he and his wife, Fran, took a train to Chicago, where they spent time in Adlai Stevenson III’s office working with Newton Minow and others on funeral arrangements before taking a flight to Washington, DC, to attend a service for Stevenson at the National Cathedral. There, offering his condolences to Martin on the loss of his friend, President Lyndon B. Johnson said of Stevenson, “He showed us the way.” Flying back on the presidential plane taking Stevenson’s body home to Illinois, Martin fell into a conversation with his friend and fellow Stevenson speechwriter Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who told Martin he should write a biography on the two-time Democratic presidential candidate.

At first, the Stevenson family turned to another person close to their father, Walter Johnson, a longtime University of Chicago history professor, as its choice to write the definitive Stevenson biography. Johnson certainly had the knowledge to accomplish the task, as he had been national cochairman for the movement to draft Stevenson as the Democratic presidential candidate in 1952 and became a close friend of the former governor.

Instead of tackling a biography, however, Johnson decided to serve as editor of a collection of Stevenson’s letters, writings, and speeches. “I felt it was time to get the solid material out,” Johnson later said. “When I began I was thinking of two or three volumes. But there was so much good material, and it soon became evident that it would require several more volumes.” The Papers of Adlai Stevenson, published from 1972 to 1979 by Little, Brown and Company, grew to eight volumes under Johnson’s editorship, assisted by Carol Evans, Stevenson’s secretary for many years.

Martin and

Nipp copied several hundred thousand pages of Stevenson’s papers, placing the

copies into looseleaf binders, each containing upwards of two hundred pages.

They numbered the binders and gave each one a special symbol designating

whether it contained correspondence, speeches, or other material. “We indexed

the copies, making an average of perhaps a thousand 5-by-8-inch cards on each

of the sixty-five years of his life, and arranged them chronologically,” said

Martin, who used the cards to write the rough draft, as they guided him to

material in the binders. “I write from the actual documents,” he noted. Martin

acknowledged that there was “a certain amount of accountancy to this type of

research,” but it was the way he worked. “It’s clumsy, it’s awkward, it’s

slow—it takes a lot of time—but you don’t make many mistakes this way,” he

noted. “And that’s the whole purpose.”

To fill in any

gaps in the information, Martin interviewed, in all, nearly two hundred people

involved in Stevenson’s life, dictating his interview notes and indexing them

in binders as well. The interviews included some he did in the summer of 1966

in Bloomington, Illinois, with Stevenson’s family and friends. These were

especially important because Martin believed nobody could understand Stevenson

unless they understood the town where he grew up. “It was there that I

discovered that Stevenson’s childhood, far from the happy time usually

pictured, had been a horror,” said Martin, including a tragedy in which

Stevenson accidentally killed a young friend with a rifle.

In the fall of

1966 Martin and his family moved to Princeton, New Jersey, and it was there

that he realized the “generous” royalty advance, which he had invested “for my

future,” and research grant he had received from Doubleday would not be enough

to finish the book (Martin had originally estimated it would take him three

years to write; it ended up taking a decade to accomplish).

Looking for

supplementary income (he estimated it would cost him $30,000 more in research funds

to complete the Stevenson biography), Martin thought of writing once again for the

national magazine market, writing Olding that he did not mind borrowing “more

money from the bank to carry expenses if there seems a good chance of writing

pieces that will sell for enough to repay the loans and keep me going.” Martin,

however, had the good fortune to receive a one-year appointment as a visiting

professor in public affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and

International Affairs at Princeton. “After that, Arthur Schlesinger had me

appointed visiting professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of

New York, where he himself now taught,” said Martin. He commuted to CUNY from

Princeton to teach his seminar, which dealt with the limits of American power

in foreign policy.

When

he began his work on the book, Martin expected it should take him three years

to finish. It took him far longer than that because of the great volume of

material he had uncovered about Stevenson. “I have to say that I came away from

the whole exercise admiring him more than I had when I began,” Martin said of

his subject. “I always knew he had political courage—I was with him when he

attacked [U.S. Senator Joseph] McCarthy and President [Dwight] Eisenhower

wouldn’t,” said Martin. “But I didn’t know how miserable, how horrible his

private life had been. I learned he also had private courage.”

Stevenson

had to deal with a sometimes traumatic childhood, “a foolish father, a

pretentious and suffocating mother, a domineering older sister, a disastrous

marriage, and, despite all the friends and comings and goings, an essentially

lonely life,” Martin said. His subject never complained about these hardships,

assuming, Martin noted, that a person’s private life was supposed to be

torture.

On

June 5, 1970, Martin, who averaged writing fifty pages a day, finally finished

the rough draft of his manuscript, which ran more than 16,000 pages and

contained some two and a half million words. “I write a long, awkward—and

lousy—rough draft,” Martin noted. “It’s simply an attempt to get facts down in

some order.” For the next year and a half, he spent his time in cutting and

rewriting the manuscript into a semifinal draft of approximately 3,200 pages,

or nearly a million words.

Martin

spent another three years clearing the manuscript with people he had promised

to show it to in return for their cooperation (among them George Ball, Arthur

Schlesinger Jr., Theodore White, Jane Dick, and Newton Minow), and obtaining

clearances for quotations from letters other people had written to Stevenson,

including such important figures in his life as Jacob Avery, Agnes Meyer, Carl

McGowan, Dore Schary, Wilson Wyatt, Louis Kohn, John Kenneth Galbraith, and

many others.

Although

some biographers paraphrase letters written to their subject in an attempt to

avoid the trouble of seeking permissions, Martin wanted to include verbatim quotes

from the letters, especially those from Stevenson’s female admirers, in order “to

preserve the flavor of their friendships.”

Final approval also had to be

obtained through negotiations with Stevenson’s eldest son, Adlai III—meetings

that included Minow as potential arbiter, and sometimes included Martin’s

editors from Doubleday, Samuel S. Vaughan and Ken McCormick. There were times

when Martin lost his patience and wondered if he was in danger of writing a

book by committee. “If we make this Stevenson book so that it pleases

everybody,” Martin wrote his agent Dorothy Olding, “we will not have a book

worth reading.”

The

storm passed, however, and Martin believed he had endured the troubles for a

good cause. “He [Adlai III] raised numerous objections, but we never were

forced to arbitration,” Martin said. Most of the younger Stevenson’s protests

involved the book’s explorations of his father’s relations with his female

friends, some ill-timed statements Stevenson had uttered about Jews, and his

feelings about African Americans. “I must say I thought young Adlai behaved

well; I am not sure I would want to read a candid biography of my own father,”

Martin said. “In any case, he did not gut the book, nor did I falsify it.”

When

he wrote the rough draft, Martin had, he confessed, been too keenly aware of

his status as a Stevenson partisan, and, consequently, to be objective, “had

been hypercritical of him,” focusing too much attention on his subject’s flaws

and weaknesses. This caused a reader of one of the drafts to tell Vaughan that

he believed the author did not like his subject. Adlai III’s critical comments

and suggestions for changes, which were adopted in the final draft, helped to

restore balance to the book, Martin said. It had not always been possible to

unravel all the complexities of Stevenson’s life in writing the biography of

this “sometimes ambiguous man,” but Martin believed he had answered all the

important questions.

The

manuscript for the Stevenson biography proved to be too long to publish in one book,

so Doubleday released the book in two volumes: Adlai Stevenson of Illinois (1976), covering his life from birth to

his first presidential campaign in 1952, and Adlai Stevenson and the World (1977), exploring Stevenson’s career

after the 1952 campaign up until his death in 1965 and published just

twenty-five years after Martin had first met him; together the books became

known as The Life of Adlai Stevenson.

No

stranger to biography, Schlesinger praised the books as “superb” and complimented

his former speechwriting partner for his ability to combine “affection,

insight, and objectivity” into what he regarded as “one of the greatest

American political biographies of the [twentieth] century.” Taken in full, the

more than 1,600 pages produced by Martin represented, noted Jeff Broadwater, a

subsequent Stevenson biographer, one of the “most impressive pieces of

detective work in the history of American biography,” an opinion, with some

reservations about the books’ relentless amount of detail, that was shared by

many other reviewers.

As John Kenneth Galbraith noted in his review of the first volume in

the New York Times Book Review,

Martin had been able to organize the vast amount of material on Stevenson into

“a far more coherent and interesting story than anyone would think possible. Some

writers take many words to say little; John Bartlow Martin takes many words,

but fewer than would be supposed, to say everything.” There was no malice or

meanness of thought in the book, and Galbraith said that Martin never allowed

his friendship with Stevenson to affect his narrative.

Although

not always flattering to a man Martin unabashedly considered to be one of his

heroes, the books represented an honest and unflinching look at one of the

leading U.S. politicians and statesmen of the twentieth century. The striking

and rigorously documented biography demonstrated to all who read it that

Stevenson’s polished speeches, his candor, and his forthrightness had worked

together to elevate the tone of America’s politics, according to a review in Time magazine. “He [Stevenson] set a

standard that later presidential aspirants have yet to match,” the reviewer for

Time concluded. Martin’s former

hometown newspaper, the Indianapolis Star,

gave him the highest compliment a biographer could receive when its reviewer

noted, “After reading Martin’s book, one can say with some degree of

satisfaction that he knows Adlai Stevenson—knows him, in fact, about as well as

he could have been known as a living person.”

Martin

had started work on the Stevenson biography while still in his fifties—a time,

he said, when a person is expected to earn his highest income and do his most

important work. He spent this vital period of his life immersed in writing

about Stevenson, and never had any regrets about his decision. “I’ve heard it

said that some writers who spend so long on a biography become bored with their

subject, or, worse, come to resent him for taking so much of their lives to

write his,” said Martin. “Luckily I escaped both infections.”

After

the dissatisfaction he had experienced while working as a speechwriter for

George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign, Martin had been inspired in

writing his book by the pleasant memories of his days with Stevenson during the

Illinois governor’s 1952 run for the presidency, marked as it was by “a sort of

ebullience, a freshness, a verve” not seen since in politics. Stevenson took

politics “out of the gutter,” Martin said, and believed it to be “a high

calling, and that showed through in the way he handled himself as a politican.

I think that was the thing that attracted all of us to him in the first place.”

Martin’s

experience with the Stevenson biography had its setbacks. Both volumes were

“widely and favorably reviewed,” but sales were only modest, Martin noted. He

also shared Fran’s disappointment that neither volume won a Pulitzer Prize or a

National Book Award. Martin came to believe that if he had written the

biography fast and it had been published in one volume shortly after

Stevenson’s death, it probably would have become a best-seller and won at least

one major honor. “On the other hand,” Martin said, “it would have been a very

different book.”

The

enormous amount of documentation he uncovered contributed to the biography’s

length, but it did not overwhelm him, Martin said. He always tried to remember

that he, alone, had complete access to all of Stevenson’s papers and he owed an

obligation to history to provide a complete view of the former governor’s life.

“Adlai Stevenson was one of the most important figures in my life,” Martin

said. “In life, he gave me a great deal, and I like to think I helped him.”