Instead

of a bland rendition of profit and loss, however, Columbia employees learned

they were to be part of an experiment in workplace democracy, an effort to

create “an industry of the worker, by the worker and for the worker.” The

employees, of which there was only one with a high school education, were to be

responsible for determining the length of time they worked, how much they were

paid, their share of production, and all other policies involved in running a

business. They also shared in any profits—an almost unheard of business

practice at that time—and eventually used them to buy, through stock held

collectively, the firm in which they toiled.

Initially,

the plan met with, at best, skepticism from those who would be its chief

beneficiaries. “Those [workers] who understood did not believe me, and very few

understood,” noted the plan’s architect, Columbia president William Powers

Hapgood. “Why should they? Their own experiences, as well as those of their

forefathers, told them it was all a lie.” Hapgood, part of a trio of remarkable

brothers that included Norman, journalist and editor at Collier’s National

Weekly and Harper’s Weekly, and Hutchins, author and bohemian,

struggled mightily over the next few years to convince the company’s workers of

his sincerity and to inspire confidence in their own abilities. His efforts,

including lending a hand on the shop floor by assisting the head cook, produced

dividends; by 1930 the company’s approximately 150 employees collectively

controlled most of the the firm’s voting stock.

Although

the workplace democracy ultimately collapsed from within, due in part to forces

unleashed by Hapgood’s own son, Powers, the Columbia experiment focused

nationwide attention on Indiana as William Hapgood and his employees attempted,

through trial and error, to develop “a new kind of association between workers

and stockholders, technicians and the rank and file.”

Born

in Chicago on February 26, 1872, William Powers Hapgood was the youngest of

three sons (a fourth child, a daughter, died at age ten) raised by Charles H.

and Fanny Louise (Powers) Hapgood. A successful plow manufacturer, Charles

moved his family to Alton, Illinois, in 1875. An admirer of agnostic

freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll, Charles attempted to instill in his offspring

“an acute distaste for moral softness,” noted eldest son, Norman. Still, his

father’s tenacity about principles was neither sour nor narrow, but a broad

approach allowing his sons the freedom to experience life and decide for themselves

on the need for such values as industry, frugality, and truth. Hutchins

recalled that his father, the hard-working businessman, was the first person he

ever heard “talk sympathetically about socialism, the ultimate advent of which

he predicted and would have welcomed.”

Born

in Chicago on February 26, 1872, William Powers Hapgood was the youngest of

three sons (a fourth child, a daughter, died at age ten) raised by Charles H.

and Fanny Louise (Powers) Hapgood. A successful plow manufacturer, Charles

moved his family to Alton, Illinois, in 1875. An admirer of agnostic

freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll, Charles attempted to instill in his offspring

“an acute distaste for moral softness,” noted eldest son, Norman. Still, his

father’s tenacity about principles was neither sour nor narrow, but a broad

approach allowing his sons the freedom to experience life and decide for themselves

on the need for such values as industry, frugality, and truth. Hutchins

recalled that his father, the hard-working businessman, was the first person he

ever heard “talk sympathetically about socialism, the ultimate advent of which

he predicted and would have welcomed.”

Growing

into a lively, athletic young man who termed sports as “the most interesting

activity of my early life,” William, like his brothers, received his education

at Harvard University. Unlike his brothers, who had worked on the editorial

side of the Harvard Monthly while at the Boston university, Norman as

editor and Hutchins as a writer, William served as the periodical’s business

manager. His interest in the commercial realm continued after his graduation

when he became an assistant shipping clerk in November 1894 at Franklin

MacVeagh Wholesale Grocery in Chicago, a firm owned by a friend of Charles

Hapgood.

Seeking

new challenges William, who had married Eleanor Page in 1899 and whose son,

Powers, was also born that year, convinced his now retired father to buy in

1903 the Mullen-Blackledge Canning Company, located on South Meridian Street in

Indianapolis. The new Columbia Conserve Company, with brothers William, Norman,

and Hutchins as stockholders, had an inauspicious start; by 1910 the firm had

left Indianapolis because of financial difficulties and moved its operations to

an abandoned factory purchased by Charles for $5,000 in Lebanon, Indiana.

Reincorporated with $125,000 in capital stock, the company returned to Indianapolis

in 1912 and set up shop at 1735 Churchman Avenue.

By

1916 Columbia had “brought a great increase in our sales with quite as great an

increase in the net profits,” said William Hapgood. Buoyed by this success, he

decided that the time seemed favorable to unveil his plans for moving Columbia

from “an autocratic to a democratic form of government.” For a

number of years, Hapgood had discussed and debated with his brothers and

friends the idea of installing democracy in the workplace. He had been troubled

by the fact that complete control of the company had been vested in him “not by

superior ability necessarily, but by property rights,” since the Hapgood family

owned Columbia’s entire stock.

William

Hapgood’s initial plan for Columbia’s employees involved creating a ten-person

committee, three appointed by the firm’s owners and seven elected from the

plant, to oversee such issues as wages, hours, hiring (including supervisory

personnel like foremen), and other plant policies. Hapgood retained the authority,

withdrawn a year later, to veto the committee’s decisions, but such an action

could be overruled by a two-thirds vote by that body. One of the committee’s

first acts, done without Hapgood’s presence, reduced working hours from

fifty-five to fifty hours per week—an action that caused some local

businessmen, astonished that employees could set their own hours, to dub

Columbia the “rocking chair cannery.”

In

1924 the committee and another workers’ group elected to act as advisers to the

committee were merged into what came to be known as the Council. Any full-time

worker who attended a Council As Columbia employees gained more confidence in

their new work situation, the Council became more daring in its actions. One of

the factory workers questioned Hapgood about why only a few employees at the

firm were paid by the week and retained by the year, while others were paid by

the hour and kept employed only as long as their time could be fully occupied

(regularity of employment was always a problem in the seasonal canning

industry). “He asked if I had more concern for the needs of my family than he

had for his,” Hapgood recalled, “and what the reason was for the present system

of special privileges for a few and ruthlessness to the majority.” Acting on

the worker’s concern, the Council did away with the time clock and placed most

of the wage force at the Indianapolis company on a salary.

In

1924 the committee and another workers’ group elected to act as advisers to the

committee were merged into what came to be known as the Council. Any full-time

worker who attended a Council As Columbia employees gained more confidence in

their new work situation, the Council became more daring in its actions. One of

the factory workers questioned Hapgood about why only a few employees at the

firm were paid by the week and retained by the year, while others were paid by

the hour and kept employed only as long as their time could be fully occupied

(regularity of employment was always a problem in the seasonal canning

industry). “He asked if I had more concern for the needs of my family than he

had for his,” Hapgood recalled, “and what the reason was for the present system

of special privileges for a few and ruthlessness to the majority.” Acting on

the worker’s concern, the Council did away with the time clock and placed most

of the wage force at the Indianapolis company on a salary.

Columbia’s

employees received no overtime pay under the salary arrangement, but did

receive paid vacations and time off for sickness and other necessary absences.

Other fringe benefits included: a pension plan; medical, dental, and hospital

care; accident insurance; free meals in the company’s cafeteria; free classes

in various subjects at the plant; and reimbursement to workers hired from out

of town for their traveling expenses to move to Indianapolis.

With

the Great Depression making itself felt on business, Columbia began to

experience problems. Pledged to keep employees on the job even if there were no

orders to fill, the firm attempted to stem the flow of red ink by cutting salaries.

At the end of May 1931, with sales shrinking, salaries were reduced by 50

percent. As the depression’s effects worsened, that figure grew to reach 75

percent.

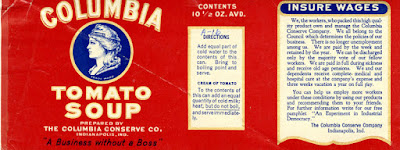

Trying

to stem the tide of red ink, the company, in late 1932, embarked on a far-ranging

plan to market its product under its own label. Workers, who in some instances

had endured paydays without pay, balked at the expense of such a program,

including the $2,000 a year paid to Norman for publicity and advertising work.

Among the most vocal critics were former union leaders brought into the firm by

Hapgood’s son, Powers, who had spent his life fighting for the rights of

working men and women as a union organizer.

Powers

joined his father’s company late in 1929, bringing with him his brother-in-law

Dan Donovan, Leo Tearney, and John Brophy. Norman, who was not “enthusiastic”

about the hires, claimed that the men were all dedicated to the belief that

while employed at Columbia they “could carry out ideas for which they had

become accustomed to doing political combat either in the Socialist party or in

left-wing labor factions.” Although Powers Hapgood himself supported the

publicity campaign, Brophy and Donovan attacked the plan, blaming it for the

reduction in workers’ salaries, and wondered why the savings could not come

from administrative expenses.

Matters

came to a head at the end of January 1933 when the company’s board of directors

acted against the Columbia Council’s wishes and summarily fired Brophy,

Donovan, and Tearney. Believing that the men had been unfairly dismissed,

Powers, still recuperating from being wounded in an accidental shooting at the

family’s farm, quit his job at Columbia. “Poor Powers was terribly torn,”

Brophy said, “having to choose between his friend and his father, and able to

see some right on both sides.”

Hoping

to bring some kind of order to a chaotic situation, William Hapgood agreed to

place the matter before an impartial outside committee that included professors

Douglas and Jerome Davis and liberal churchmen Sherwood Eddy and James Myers.

The Committee of Four, as it came to be known, ruled that the three employees

should be reinstated with back pay “on the condition that they agree to a

common loyalty to the policies of Columbia and to do everything they can to

promote its prosperity.”

For Hapgood,

however, there existed in his mind no room for such a compromise. He threatened

to resign from the company if the Council did not agree to get rid of Brophy

and Donovan. The Council acquiesced to Hapgood’s wishes. Defending his actions,

Hapgood said that in a democracy, either industrial or political, charges of

bad faith are often made during times of “stress and confusion.”

Although

Hapgood received sharp criticism from liberal publications for his seemingly

capricious actions, Columbia eventually regained its footing following what he

later called the “disheartening and disintegrating conflict,” even making a

profit for a time. The experiment in workplace democracy survived until 1942,

when workers, who still controlled approximately 60 percent of the company’s

stock, went on strike over wage issues. In 1953 Hapgood, who had become blind

from trachoma, sold Columbia to John Sexton and Company, a Chicago wholesale

grocery chain.

Tragedy

plagued the Hapgood family in later years. Powers, who had continued to work

for the union’s cause as a regional organizer for the Congress of Industrial

Organizations, died in 1949 due to a coronary blockage as he was driving to the

family’s farm. He was forty-nine years old.

A

few years before, William Hapgood reflected about the Columbia experiment to reporter and author John Bartlow Martin, saying: “I don’t know that we convinced anybody that a producers’

cooperative would work, don’t even know that we convinced ourselves.” Hapgood,

who died in 1960, lived long enough to see the fringe benefits enjoyed by his

Columbia employees become a common fact of life for workers in other

industries. As his private secretary Dorothea Nord Hold once told him, the

experiment at the central Indiana canning factory “did not just happen, but due

to your background, education and philosophy of life, you had to do it. You had

no other choice.”

No comments:

Post a Comment